Content

An engaging story will attract readers and make them curious to read more. To write a good story, you need to be ready to tweak it so that each sentence has meaning. Start by building characters and outlining the story, then start writing the first draft from the opening to the end. Once your first draft has taken shape, you can refine it using a number of writing techniques. Finally, review to complete the final draft.

Steps

Part 1 of 4: Character development and storyline

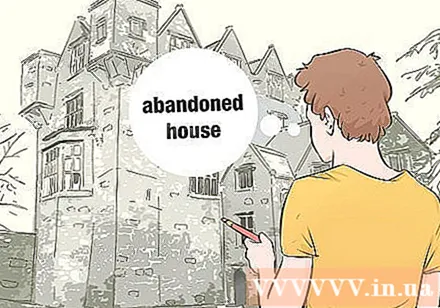

Brainstorm to find a good character or storyline. Your story can come from a character you think is interesting, a fascinating location, or a concept that makes up a plot. Write down your thoughts or mind mapping to form ideas and choose one of them to develop into a story. Here are a few suggestions to try:

- Experiences in your life

- A story with hidden, scary or mysterious content

- A story you have ever heard

- Family story

- A "what if" scenario

- A current story

- A dream

- An interesting person you've ever met

- Pictures

- Art topic

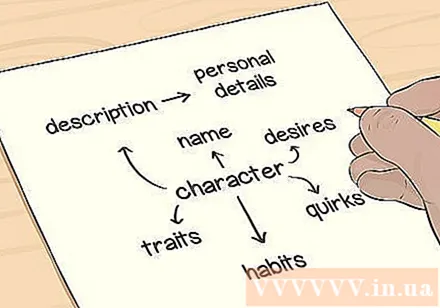

Build characters by making character sketches. The character is the most important element in the series. Readers will empathize with the characters, and the characters will lead to your story. Create a profile for characters by naming them, describing personal details, appearance, features, habits, desires, and interesting habits. Write down as many details as possible.- Sketch the main character first. Next up is the sketches of other main characters, such as villains. Characters are considered major if they play a major role in the story, such as influencing the main character or affecting the plot.

- Ask yourself what your characters want or what their motives are, then build a storyline around the character and work it out in the direction of either getting what they want, or not.

- You can create sketches for your own characters or find templates online.

Choose a setting for the story. The setting is the time and place where the story takes place. It has to affect the story in some way, so you need to choose an additional context for the story. Consider how the setting impacts the characters and their relationships.- For example, the story of a girl who dreamed of becoming a doctor when told in the 1920s would differ from that of 2019. The character will have to overcome other obstacles, such as gender bias. , depending on the context. However, you can use this context if your subject is perseverance, as it allows you to portray a stubborn character who chases his dream against social prejudice.

- As another example, the setting of a camping story deep in an unfamiliar forest creates a different mood than when placed in the protagonist's backyard. A forest setting can focus on the protagonist's viability, while a backyard setting can be aimed at the character's family relationships.

Warning: When choosing a scene, you should be cautious about times or places that are unfamiliar to you. Details are easy to go wrong, and the reader will probably spot your error.

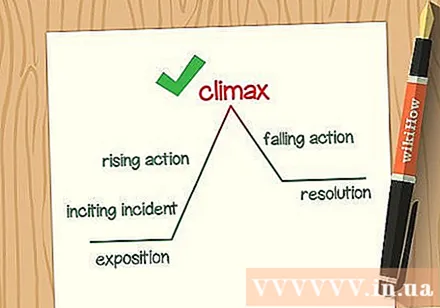

Outline the main lines of the plot. A plot sketch will help you know what to write next. Besides, it also helps you fill in the gaps in the storyline before you start writing. You can use brainstorming and character sketching to build the storyline. Here are a few ways to do this:

- Create plot chart including introduction, event beginning, conflict surges, climax, descending conflict, ending.

- Create a traditional outline with key points for each scene.

- Summarize each plot and turn it into a bulleted list.

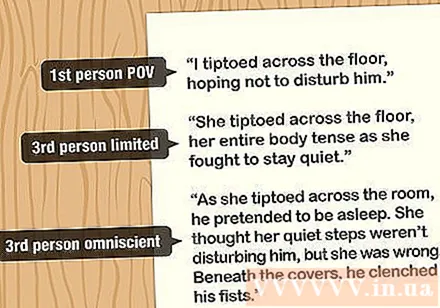

Choose the angle of view in the first or third person. Viewing angles can completely change the perspective of a story, so choose wisely. Choose the angle of view in the first person to follow the story. Use a limited third perspective if you want to focus on one character but want to keep some distance to provide your own interpretation of the details. Another option, you can use the third person smoothly if you want to share everything that happened in the story.

- Viewing angle in first person - Each character will tell the story from their perspective. Since the story is told from the subjective point of view of the first person, their account may not be correct. For example, "I tiptoed slightly on the floor, hoping he wouldn't wake up."

- The viewing angle in the third person is limited - A narrator narrates the events of the story, but the perspective is limited to one character. Using this perspective, you cannot add other characters' thoughts or feelings but still include your interpretations of the setting or events in the story. For example, "She crept on the floor, her whole body tense, trying her best not to make a sound."

- The viewing angle of the third person is clear - A narrator witnesses all narrations of all events that happened in the story, including the thoughts and actions of each character. For example, “When she tiptoed across the room, he pretended to sleep. She thought her smooth footsteps didn't wake him up, but she was wrong. Lying under the blanket, he was clenching his fists. "

Part 2 of 4: Draft stories

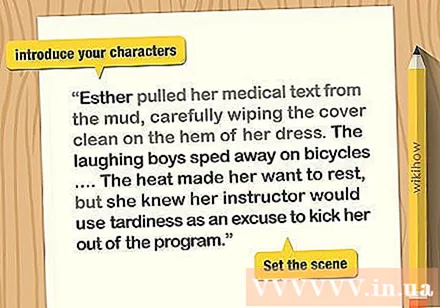

Set up the scene and introduce the characters in the opening. Allow two or three paragraphs to immerse your readers in the context. First, you put the character in the context, followed by a brief description of the place and combined with other details to introduce the era in which the story is going. Provide just enough information for the reader to visualize the picture.

- You can open the story like this: “Esther picked up the medical book out of the mud and carefully wiped the cover with the hem of her dress. The smiling boy cycled away, leaving her alone to walk the remaining two kilometers to the hospital. The sun cast sunlight on the soggy landscape, turning the morning puddles into a wet midday mist. The heat made her just want to stop, but she knew the instructor would make the excuse that she was late to knock her out of the show. ”

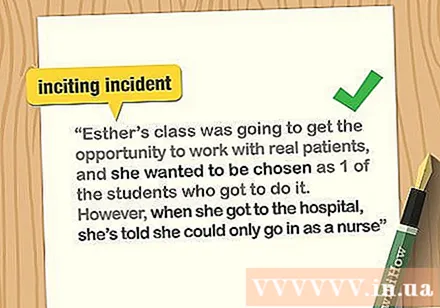

Introduce the problem in the first few paragraphs. The problem in the story will act as a starting event for the storyline and keep the interest of the reader. Think about what your character wants, and why they didn't get it. Next, let's create a scene depicting them dealing with a problem.

- For example, let's say Esther's class is about to have a chance to practice with a patient, and she hopes to be one of the selected students, but when she arrives at the hospital, she learns that she can only practice with role as a nurse. This detail sets up the storyline of Esther's struggle to practice as a doctor.

Bringing conflict high into the middle of the story. Describe the character trying to solve the problem. To make the story more engaging, you should include two or three challenges they face as they reach the climax of the story. This section will give the reader a thrill before you reveal what the story is about.

- For example, Esther could go to the hospital as a nurse, find co-workers, get dressed, almost be found out, and then meet a patient in need of treatment.

Create a climax to solve problems. The climax is the climax of the story. You need to create an event that forces your character to fight for his goals, then show the character either succeed or fail.

- In Esther's story, the climax can happen when she is caught trying to treat a patient who has just collapsed. When she was dragged away by hospital security staff, she shouted out an accurate diagnosis that a senior doctor overheard ordered her release.

Use the descending conflict section to bring the reader to the end. The diminishing conflict should be short, because the reader will no longer be compelled to read after the climax. You can write two paragraphs to close the storyline and summarize what happened after the problem solving.

- For example, a certain senior doctor might commend Esther and offer to be willing to be her mentor.

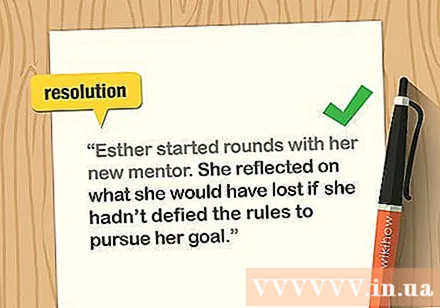

Write the ending that gives the reader something to ponder. In the first draft, don't worry about creating a great ending. Instead, focus on presenting the character's theme and suggesting the next action. This will make the reader think about the story.

- Esther's story may end with her starting to work with her new instructor. She could contemplate what she would have missed if she hadn't disregarded the rules to pursue her goal.

Part 3 of 4: Sharpening the story

The beginning of the story is as close to the story as possible. The reader does not need to know all of the events leading up to the problem the character is facing. They just want to see a snapshot of the character's life. You should choose a trigger that can quickly lead the reader into the storyline. So your story doesn't move too slowly.

- For example, opening the story with Esther on her way to the hospital would be better than the scene where she entered medical school. It might have been even better if the story unfolded when she arrived at the hospital.

Use dialogue to reveal a bit about the characters. The dialog pieces will separate the paragraphs to help readers slide down the page from above. Furthermore, they will also allow you to express your characters' thoughts with their own words without the need for a lot of inner monologues. You can use the dialogue throughout the story to convey your character's thoughts. However, make sure that each piece of dialogue leads the plot.

- For example, the following conversation describes Esther's disappointment: “But you're the best student in the class,” Esther pleaded. "Why are other friends being examined for patients, and I can't?"

Create tension with bad situations that happen to your character. It is difficult to put the character in harsh situations, but otherwise your story will be very boring. Put up obstacles or arduous challenges to separate them from what they want. That way, you will have problems to solve and help the character reach his dream.

- For example, not being able to go into the hospital as a trainee was a terrible thing for Esther. Similarly, the situation where she was grabbed by the security staff at the hospital was also a frightening experience.

Stimulate the reader's five senses with sensory details. Use sight, hearing, touch, smell, and taste to guide readers into stories. The context of the story will be more lively with the sounds, smells and feelings that the reader feels. These details will make your story more engaging.

- For example, Esther can react to hospital odors or beep sounds on appliances.

Invoke emotions to help the reader relate to the story. Try to make the reader feel the character's emotions. You can do this by connecting the things the character is going through with the common things in life. Emotions will draw readers into the story.

- For example, Esther worked hard, and then was rejected because of a technical problem. Most readers have experienced such a feeling of failure.

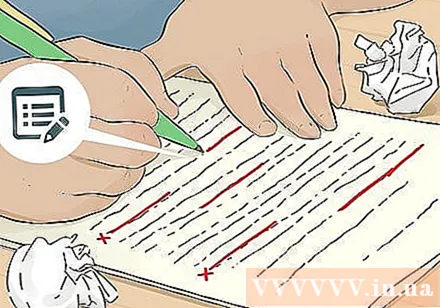

Part 4 of 4: Review and complete story

Rest for at least a day before reviewing the story. It is unlikely to be effective if you revisit the story as soon as you finish writing the manuscript, because then you will not be able to detect the bugs and holes in the plot. Let's put the story aside for at least a day so that it can be viewed under a new perspective.

- Printing stories on paper can also help you review the story in a new angle. Try this method when reviewing the story.

- A little rest is fine, but don't take it long enough to lose interest.

Read the story out loud to hear which passages need editing. When you read it out loud, you will look at your story from a different angle. This will help you spot non-smooth passages or sentences that sound like a mess. Read the story to yourself and pay attention to the areas that need editing.

- You can also read stories to others and ask them to comment.

Get feedback from other authors or regular readers. When you're ready, give your story to everyone to read, such as writing enthusiasts, instructors, classmates or your friends. If possible, bring it to seminars or critiques. Ask for the readers' honest feedback so you can edit the story for more complete.

- The people closest to you, like your parents or close friends, may not be able to provide the best response, as they are too concerned about your feelings.

- For feedback to work, you need to be receptive. If you think the story you just wrote is the most perfect in the world, you really don't need to hear a word from anyone.

- Make sure you get the right people to read the story. You probably won't get the best response if you show your sci-fi story to someone you love reading fiction.

Advice: Literature review groups can be found on Meetup.com or at libraries.

Removed any details unrelated to the character or contributed to the development of the plot. That way, you may have to cut out any paragraphs that you think are good. Readers are only interested in details that play an important role in the story. When rereading the story, make sure that each sentence is telling about a certain aspect of the character or boosting the story's course. Cut out sentences that do not serve this purpose.

- For example, suppose there is a description of Esther meeting a girl in a hospital reminiscent of her sister. While it sounds interesting, this detail does not guide the course of the story, nor does it suggest anything meaningful about Esther, so it's best to cut it off.

Lucy V. Good

Author, Writer and Screenwriter Lucy V. Hay is an author, screenwriter and blogger who has helped other authors through seminars, writing courses, and her blog. is Bang2Write. Lucy is the producer of her first two crime thrillers and crime novels, The Other Twin, being adapted to the screen by Agatha Raisin, Sky's (Free @ Last TV) Emmy award-winning filmmaker.

Lucy V. Good

Author, Writer and Script EditorConsider submitting stories to short story creation competitions. Many short story creation competitions have awards of some form, such as your story being published in a collection, or you get the chance to meet with a representative for a chat. These awards will be useful to you in the future. If your story is printed in multiple anthologies, you will get bonus points for submitting proposals to agents. Some contests such as the Bridport Prize and the Bath Short Story Award in the UK are very prestigious - if you can win a prize in such contests, you will be seen as a talented writer.

advertisement

Advice

- Take your notebook with you wherever you go so you can write it down whenever an idea flashes.

- Don't start editing the story right after you finish writing the draft, as it will be difficult to spot mistakes and holes in the plot. Wait a few days until you can review your story with fresh eyes.

- Write drafts before completing your final draft. This will greatly help with the editing process.

- Conversations and details are the key to writing an engaging story. Put your readers in the shoes of your character.

Warning

- Don't drag the story too long by including information that is unnecessary for character development or plot development.

- Remember to write sentences of different lengths.

- Don't copy literature from other books. This action is plagiarism.

- Do not write while editing, as this will slow down your writing speed.