Author:

John Pratt

Date Of Creation:

14 April 2021

Update Date:

1 July 2024

Content

- To step

- Part 1 of 3: Preparing to write the vignette

- Part 2 of 3: Brainstorming ideas for the vignette

- Part 3 of 3: Writing the vignette

A vignette is a short piece of literature used to add depth or understanding to a story. The word "vignette" comes from the French word "vigne", which means "little vine." A vignette can be a "little vine" of a story, like a snapshot of words. A good vignette is short, to the point and full of emotions.

To step

Part 1 of 3: Preparing to write the vignette

Understand the purpose of a vignette. A vignette should express a particular moment, mood, aspect, setting, character or object. Above all, it should be brief, but descriptive.

Understand the purpose of a vignette. A vignette should express a particular moment, mood, aspect, setting, character or object. Above all, it should be brief, but descriptive. - In terms of length, a vignette is usually between 800-1000 words, but it can also be a few lines or less than 500 words.

- A vignette usually has 1-2 short scenes, moments or impressions about a character, an idea, a theme, a setting or an object.

- You can use a first, second or third perspective in a vignette. However, most vignettes are written from one perspective, rather than alternating a few. Remember that you have limited space on the page for the vignette, so don't waste your precious time confusing your reader with too many perspectives.

- The vignette format can also be used by physicians to prepare a report on the status of a patient or procedure. In this article, we are only talking about a literary, not a clinical vignette.

Don't feel limited to one structure or style in a vignette. A vignette is an open form.This means that you don't have to write within a particular structure or plot. So you can have a clear beginning, middle and end, or you can skip the beginning and end altogether.

Don't feel limited to one structure or style in a vignette. A vignette is an open form.This means that you don't have to write within a particular structure or plot. So you can have a clear beginning, middle and end, or you can skip the beginning and end altogether. - A vignette also does not require a main conflict or a resolution of a conflict. This freedom gives some vignettes an unfinished or unresolved tone. But unlike other traditional story forms such as the novel or the short story, a vignette does not have to tie all loose ends together.

- In a vignette you are not limited to a particular genre or style. So you can combine elements of horror and romance, or you can use poetry and prose in the same vignette.

- You may use simple and minimalist language or lavish, detailed prose.

Remember the only line of the vignette:create an atmosphere, not a story. Because there is limited space in a vignette, it is important to show, not tell the reader. So avoid background stories or explanations in a vignette. Instead, focus on taking a snapshot of a character's life or setting.

Remember the only line of the vignette:create an atmosphere, not a story. Because there is limited space in a vignette, it is important to show, not tell the reader. So avoid background stories or explanations in a vignette. Instead, focus on taking a snapshot of a character's life or setting. - A vignette can also be in the form of a blog post or even a Twitter post.

- Usually shorter vignettes are more difficult to write, because you have to sketch an atmosphere in a few words and evoke a response from your reader.

Read examples of vignettes. There are several great examples of vignettes, ranging from very short to long. For instance:

Read examples of vignettes. There are several great examples of vignettes, ranging from very short to long. For instance: - The Vine Leaves Journal publishes vignettes, both short and long. One of the entries in their first issue is a two-line vignette by the poet Patricia Ranzoni called "Flashback": "the softness from dialing the phone / is like lifting the lid to my music box.”

- Charles Dickens uses longer vignettes or "sketches" in his novel "Sketches by Boz" to explore scenes and people in London.

- Writer Sandra Cisneros has a collection of vignettes entitled "The House on Mango Street," narrated by a young Latina girl living in Chicago.

Analyze the examples. Whether the vignette is two lines long or two paragraphs, it must convey a certain emotion or mood to the reader. Take a good look at how the sample vignettes use tone, language, and mood to evoke emotions in the reader.

Analyze the examples. Whether the vignette is two lines long or two paragraphs, it must convey a certain emotion or mood to the reader. Take a good look at how the sample vignettes use tone, language, and mood to evoke emotions in the reader. - The two-line vignette by the poet Patricia Ranzoni is a successful piece because it is both simple and complex. Simple because it describes the feeling you get when you enter the number of someone you would like to speak to. But complex because the vignette connects the tension of a song to the tension of opening a music box. The vignette thus combines two images to create one emotion. It also uses "softness" to describe typing the phone number, which is also consistent with the softness of a music box liner, or the soft music played by a music box. With just two lines, the vignette effectively creates a particular mood for the reader.

- In "The House on Mango Street" by Cisneros there is a sticker called "Boys & Girls". It is a longer vignette, of four paragraphs, or around 1000 words. But it sums up the young narrator's emotion towards the boys and girls near her, as well as her relationship with her sister Nenny.

- The narrator uses simple, direct language to describe the separate world of boys and girls in her neighborhood. Cisneros ends the vignette with an image that summarizes the narrator's feelings.

One day I'll have a best friend all to myself. One where I can tell secrets. One that will understand my jokes without me having to explain them. Until then, I am a red balloon, a balloon attached to an anchor.

- The image of a "balloon attached to an anchor" adds color and texture to the vignette. The narrator's sense of being held down by her sister is perfectly summed up in that final image. So the reader keeps the feeling that he is being oppressed or attached to someone, just like the narrator.

Part 2 of 3: Brainstorming ideas for the vignette

Create an association diagram. An association diagram is also known as a cluster technique. You create a cluster or group of words around a theme or an idea.

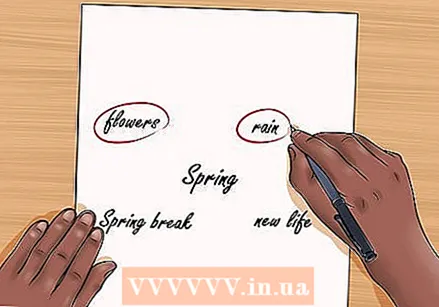

Create an association diagram. An association diagram is also known as a cluster technique. You create a cluster or group of words around a theme or an idea. - Take a sheet of paper. Write your main theme or topic in the center of the paper. For example "spring".

- Moving from the center, you write down other words that come to mind that have to do with "spring."

- For example, for "spring" you can write "flowers", "rain", "Easter holidays", "new life". Don't worry about organizing the words as you write. Just let the words flow around the main theme.

- Once you feel you have written enough words around your main theme, start clustering the words. Draw a circle around the related words and draw a line between the circled words to connect them. Do this in the other words too. Some words may not be circled, but these single words may also be important.

- Focus on how the words relate to the main theme. For example, if you've clustered a few words related to "new life," this might be a good approach for the vignette. Or if there are many clustered words related to "flowers," that might be another way of approaching "spring."

- Answer questions such as, “I was amazed by…” or “I discovered…” For example, you can look at the clustered words and notice that “I was amazed at how many times I mentioned my mother in connection with spring.” Or “I found that I was might want to write about that spring means new life. '

Write freely. Free writing is an opportunity to let your thoughts flow onto a piece of paper. Write whatever comes to your mind and don't judge what you write.

Write freely. Free writing is an opportunity to let your thoughts flow onto a piece of paper. Write whatever comes to your mind and don't judge what you write. - Take a sheet of paper or open a new document on your computer. Write the main theme at the top of your paper. Then set a time limit of 10 minutes and start writing freely.

- A good rule of thumb for free writing is not to lift your pen from the paper or your fingers from the keyboard. This means that you don't reread the sentences you just wrote or go back to a line for spelling, grammar, or punctuation. If you think you can't write anything anymore, write about your frustrations about not knowing anymore to write about your main topic.

- Stop writing when the time is up. Read the text. While it may contain some confusing or complicated sentences, there are also sentences that you like or insight that may be helpful.

- Color or underline sentences or phrases that you think will fit in the vignette.

Ask yourself the six big questions. Grab a piece of paper or open a new document. Write the main theme of the vignette at the top of the document. Then write six headlines: Who? What? When? True? Why? And how?

Ask yourself the six big questions. Grab a piece of paper or open a new document. Write the main theme of the vignette at the top of the document. Then write six headlines: Who? What? When? True? Why? And how? - Answer each question with a phrase or phrase. For example, if your topic is "spring," you can click Who? answer "my mother and I in the garden". You can on Why? answer with "A warm summer day in July when I was six". At Where? can you answer with "Miami, Florida". Why? you can answer "Because it was one of the happiest moments of my life." And How? can you answer "I was alone in the garden with my mother, without my sisters".

- Review your answers. Do you have more than one or two sentences for a particular question? Is there a question you couldn't answer? If your answers show that you know more about "where" and "why", that may be where the best ideas for the vignette are.

Part 3 of 3: Writing the vignette

Determine the style of the vignette. Maybe you want a free-style vignette where you can create a scene or describe an object. Or maybe you want a letter form or blog post for the vignette.

Determine the style of the vignette. Maybe you want a free-style vignette where you can create a scene or describe an object. Or maybe you want a letter form or blog post for the vignette. - For example, a "spring" vignette can describe a scene in the garden with your mother, among the flowers and trees. Or it could be in the form of a letter to your mother about that spring day, among the flowers and trees.

Add sensory details. Focus on the five senses: touch, taste, smell, sight, and hearing. Could some detail in the vignette be stronger describing the fragrance of a flower or the softness of the petals?

Add sensory details. Focus on the five senses: touch, taste, smell, sight, and hearing. Could some detail in the vignette be stronger describing the fragrance of a flower or the softness of the petals? - You can also add figurative language to make the vignette stronger, such as similes, metaphors, alliteration and personification. However, use these in moderation and only if you think a simile or metaphor will emphasize the rest of the vignette.

- For example, the use of the red balloon on an anchor in Cisneros 'Boys & Girls' is an effective use of figurative language. But it works well, because the rest of the vignette uses simple language, so the image at the end of the vignette sticks with the reader.

Compact the vignette. A good vignette must have a sense of urgency. This means omitting details such as what the character ate for breakfast or the color of the sky in the garden unless they are essential to the vignette. Only keep scenes and moments in it that add urgency and remove any details that slow down the pace of the vignette.

Compact the vignette. A good vignette must have a sense of urgency. This means omitting details such as what the character ate for breakfast or the color of the sky in the garden unless they are essential to the vignette. Only keep scenes and moments in it that add urgency and remove any details that slow down the pace of the vignette. - Read the first two lines of the sticker. Does the vignette start at the right time? Is there any sense of urgency in the first two lines?

- Make sure your characters meet very early on in the vignette. See if you can edit the vignette so that you set the tone in as few words as possible.