Author:

Frank Hunt

Date Of Creation:

15 March 2021

Update Date:

1 July 2024

Content

- To step

- Method 1 of 2: Brainstorming about characters

- Method 2 of 2: Using your character sketches

- Tips

Character sketches are guidelines, explorations, and even short stories essential to writers in any form. You want to develop a consistent, realistic character early on, so you know how it would behave in any situation. The best stories have characters driving the plots, not plots driving the characters, but that is only possible if you know who your characters are.

To step

Method 1 of 2: Brainstorming about characters

Start by writing about your character for 10-15 minutes. There is no right way to start a character sketch, because the characters can pop up in your head in different ways. You could see their physical appearance first, you could think of a profession or character type you want to use, or you could decide to base a character on someone you know. When designing characters, you need to set aside some time to let your imagination run wild, find your first image of the character and move on from there.

Start by writing about your character for 10-15 minutes. There is no right way to start a character sketch, because the characters can pop up in your head in different ways. You could see their physical appearance first, you could think of a profession or character type you want to use, or you could decide to base a character on someone you know. When designing characters, you need to set aside some time to let your imagination run wild, find your first image of the character and move on from there. - You are not bound by any of these first sketches. You can easily throw them all away. Like all brainstorming exercises, it's important to start by looking for ideas you love.

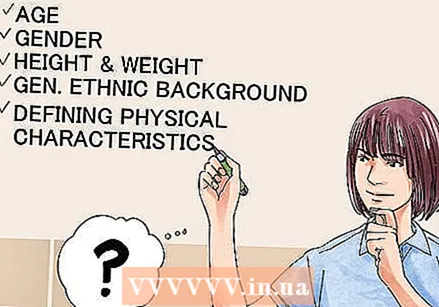

Confirm the basic physical description of the character. It is much easier to think in visual, concrete terms than to put together abstract concepts such as "friendly" or "intelligent". Most writers, and all readers, generally need some sort of image of the character they can relate to. If you are artistically inclined, you could even sketch your character first. Even if the description is sparse ("young white male"), in the final book, movie, or game, a good character sketch requires the following:

Confirm the basic physical description of the character. It is much easier to think in visual, concrete terms than to put together abstract concepts such as "friendly" or "intelligent". Most writers, and all readers, generally need some sort of image of the character they can relate to. If you are artistically inclined, you could even sketch your character first. Even if the description is sparse ("young white male"), in the final book, movie, or game, a good character sketch requires the following: - Age

- Sex

- Length and weight

- General ethnic background (eg: "tall, blond Scandinavian type")

- Defining physical characteristics (hair, beauty, glasses, typical clothing, etc.)

Consider your character's general emotions and feelings. Complex characters show a wide variety of emotions, but almost all people and characters can be simplified to 1-2 basic emotions. In general, the question of how your character stands in life is: optimistic, greedy, humorous, angry, forgetful, thoughtful, timid, creative, analytical? You want a simple guide to writing out the character - a jump point that allows you to explore the other, more complex emotions when you start writing.

Consider your character's general emotions and feelings. Complex characters show a wide variety of emotions, but almost all people and characters can be simplified to 1-2 basic emotions. In general, the question of how your character stands in life is: optimistic, greedy, humorous, angry, forgetful, thoughtful, timid, creative, analytical? You want a simple guide to writing out the character - a jump point that allows you to explore the other, more complex emotions when you start writing. - What could be the character's zodiac sign?

- How does the character deal with hardship?

- What makes the character happy? sad? Angry?

Come up with a name for your character. Sometimes the name comes easy. Sometimes this is the hardest part of the character to get around. While names can change during the writing process, there are a few different paths you can take when naming characters:

Come up with a name for your character. Sometimes the name comes easy. Sometimes this is the hardest part of the character to get around. While names can change during the writing process, there are a few different paths you can take when naming characters: - Search the internet for baby name websites. Most of these websites also categorize the names by ethnic origin, such as Japanese, Arabic, French, Russian, Hawaiian, Hindi, etc.

- Choose meaningful names. While this is somewhat out of fashion for modern literature and film, there is a rich history of well-chosen, meaningful character names. See The Scarlett Letter, or Arrested Development for various humorous or insightful names.

Determine the character's relationship with the story, the world, or the main character. Why is this character important to your book or novel? Writing a character sketch about someone generally means that he or she is vital to your story, as minor characters rarely need a character sketch. What is their relationship to the main character? How do they get involved in the story? What is their contribution to the novel?

Determine the character's relationship with the story, the world, or the main character. Why is this character important to your book or novel? Writing a character sketch about someone generally means that he or she is vital to your story, as minor characters rarely need a character sketch. What is their relationship to the main character? How do they get involved in the story? What is their contribution to the novel? - Again, this does not have to be fixed. Many writers use this space to brainstorm possible plots, conflicts or uses of the character.

Develop your own background for characters. Where did they grow up? What were their parents like? You may never use this information again, but as a writer you need to know these things to be able to write credible character. Just thinking about their childhood tells you something about their accent, values, philosophy (or lack thereof), etc. If you have trouble coming up with a backstory, start with a simple question. How did the character get to where they are when the story begins?

Develop your own background for characters. Where did they grow up? What were their parents like? You may never use this information again, but as a writer you need to know these things to be able to write credible character. Just thinking about their childhood tells you something about their accent, values, philosophy (or lack thereof), etc. If you have trouble coming up with a backstory, start with a simple question. How did the character get to where they are when the story begins? - Think of friends or acquaintances who resemble your character. What is their backstory? Read biographies or lifelike character sketches for inspiration.

Find your character's overarching motivation. What does your character want above all else? What leads or prompts him to act? These could be his principles, goals, fears or sense of duty. The best characters are forceful. That means taking steps to get what they want instead of just reacting to the world around them. This doesn't mean you can't have lazy or simple characters - The Dude from The Big Lebowski after all, just wants to rest. Don't think that a desire to keep things the same is a lack of desire - all characters long for something that will drive them through the story.

Find your character's overarching motivation. What does your character want above all else? What leads or prompts him to act? These could be his principles, goals, fears or sense of duty. The best characters are forceful. That means taking steps to get what they want instead of just reacting to the world around them. This doesn't mean you can't have lazy or simple characters - The Dude from The Big Lebowski after all, just wants to rest. Don't think that a desire to keep things the same is a lack of desire - all characters long for something that will drive them through the story. - What do they fear?

- What do they want?

- If you asked your character, "Where do you want to be in five years," what would he say?

Fill in any other details that pop up in your head. This is going to change depending on your story. What small pieces of the character make him unique? How is he different from other characters and how are they similar? This information may not last into the final project, but it will help you develop a fuller, rounder character. Some places where you could start are:

Fill in any other details that pop up in your head. This is going to change depending on your story. What small pieces of the character make him unique? How is he different from other characters and how are they similar? This information may not last into the final project, but it will help you develop a fuller, rounder character. Some places where you could start are: - What are their favorite books, movies and music?

- What would they do if they won the lottery?

- What was their major in college?

- If they could have a superpower, what would it be?

- Who is their hero?

Work out your character's personality in one or two sentences. Think of this as the character's theorem. It will be your general distillation of the character, and everything your character does should reflect this phrase. If you are not sure how a character would react to a situation, you can always return to this compact description for guidance. Look at some examples from the literature and TV for clues.

Work out your character's personality in one or two sentences. Think of this as the character's theorem. It will be your general distillation of the character, and everything your character does should reflect this phrase. If you are not sure how a character would react to a situation, you can always return to this compact description for guidance. Look at some examples from the literature and TV for clues. - Ron Swanson (Parks and Rec): An old-fashioned libertarian who works for the government, hoping to take him down from the inside.

- Jay Gatsby (The Great Gatsby): A self-made millionaire who made his fortune winning the love of his childhood sweetheart, which he is obsessed with.

- Erin Brockovich (Erin Brockovich): A confident single mom who is willing to fight for what's right, even if it's not in her best interest.

Method 2 of 2: Using your character sketches

Realize that not everything from your character sketch will make it into your project. Ultimately, a character sketch is just a guideline for your writing. If you know the underlying forces that shaped and sculpted your characters, you can write them with confidence in any situation, without telling the reader everything.

Realize that not everything from your character sketch will make it into your project. Ultimately, a character sketch is just a guideline for your writing. If you know the underlying forces that shaped and sculpted your characters, you can write them with confidence in any situation, without telling the reader everything. - That's how we understand people in real life - you may know bits of their backstory, but in the end you know them as the sum of their experiences.

- The reader doesn't need to know everything about a character to understand them, just as we don't need to know everything about our friends to enjoy their company.

Where possible, color your character through actions. Your character sketch is a list - informative, but hardly exciting. Actions are thrilling, and they show a character without resorting to `` This is Nick, he's a writer who enjoys football and hanging out with his friends. '' Instead, let Nick play football, maybe having fun on the field or having fun. talking to teammates when he should be dribbling.Instead of just saying it, find an interesting, unique way to lighten your character's inner life.

Where possible, color your character through actions. Your character sketch is a list - informative, but hardly exciting. Actions are thrilling, and they show a character without resorting to `` This is Nick, he's a writer who enjoys football and hanging out with his friends. '' Instead, let Nick play football, maybe having fun on the field or having fun. talking to teammates when he should be dribbling.Instead of just saying it, find an interesting, unique way to lighten your character's inner life. - Think of some masterful character introductions - Hannibal in Silence of the Lambs, Jung-do in The Orphan Master's Son, Lolita in Lolita - to see how actions are more meaningful than words.

Ask yourself why the character is acting like this. This is the best way to successfully move characters from your character sheet to your book or movie. You know what they look like, how they talk and what they do. To make a character really effective, you have to investigate why they are like that. The answer to this question will guide you through every scene your character appears in and help you customize your character outline as you write new plots and storylines.

Ask yourself why the character is acting like this. This is the best way to successfully move characters from your character sheet to your book or movie. You know what they look like, how they talk and what they do. To make a character really effective, you have to investigate why they are like that. The answer to this question will guide you through every scene your character appears in and help you customize your character outline as you write new plots and storylines. - Character sketches can change. As you write, you may realize that something is off or you need to adjust your character. Knowing the overarching "why" of the character will make it much easier to identify these changes.

Write a "representative incident" that your character experienced. This sounds complicated, but in reality you've seen it hundreds of times before. A representative incident is just one short story to show the reader who the character is. Often this happens shortly after a character is first introduced, and it is usually a flashback. This allows you to briefly touch on the hero's upbringing, but also to show how the character reacts under pressure.

Write a "representative incident" that your character experienced. This sounds complicated, but in reality you've seen it hundreds of times before. A representative incident is just one short story to show the reader who the character is. Often this happens shortly after a character is first introduced, and it is usually a flashback. This allows you to briefly touch on the hero's upbringing, but also to show how the character reacts under pressure. - Usually this event is related to the bigger story. For example, a romantic book can explore the character's first love, or an action story can showcase a recent mission or event.

- Try to show a story that indicates how the character will respond to the events in the story.

- If it doesn't work out, imagine your story as if this person is the main character. What details would he consider important?

Discover the character's voice. Review the character sketch and ask yourself how the character communicates by writing a practice dialogue. Have him converse with your main character or another character, and focus on making their text unique. What jargon do they use? Are they talking with their hands? Great writers are able to bring their characters to life by letting their background resonate in their way of speaking.

Discover the character's voice. Review the character sketch and ask yourself how the character communicates by writing a practice dialogue. Have him converse with your main character or another character, and focus on making their text unique. What jargon do they use? Are they talking with their hands? Great writers are able to bring their characters to life by letting their background resonate in their way of speaking. - If you were to remove all dialogue markers ("he said," she replied, "etc.), would you be able to say who is which character?

Use the first time you see a character to introduce their total impact. Readers and viewers will always remember the first impression of a character. This impression should be consistent with the character's behavior throughout the rest of the story. For example, suppose a character is normally sweet and nice, don't make her yell at someone because she's having a bad day. If a hidden temperament is part of her personality this could be perfect - but if this is an isolated incident it will confuse the reader if she's nice the rest of the story.

Use the first time you see a character to introduce their total impact. Readers and viewers will always remember the first impression of a character. This impression should be consistent with the character's behavior throughout the rest of the story. For example, suppose a character is normally sweet and nice, don't make her yell at someone because she's having a bad day. If a hidden temperament is part of her personality this could be perfect - but if this is an isolated incident it will confuse the reader if she's nice the rest of the story. - How would a character present himself at a party or meeting?

- If you were to meet this character in real life, what would be your first impression of them?

Keep character sketches short and sweet when putting together a "treatment". A treatment is a brief overview of your book, film or TV series, to sell the story. They outline the plot, tone and descriptions of the characters. If you are writing a treatment, limit your character sketch to the essentials. You don't want to share all the quirky facts with producers or publishers, just enough to intrigue them and give them a general overview. Include only the essentials, plus 1-2 short details to make a character unique. Consider the following to include:

Keep character sketches short and sweet when putting together a "treatment". A treatment is a brief overview of your book, film or TV series, to sell the story. They outline the plot, tone and descriptions of the characters. If you are writing a treatment, limit your character sketch to the essentials. You don't want to share all the quirky facts with producers or publishers, just enough to intrigue them and give them a general overview. Include only the essentials, plus 1-2 short details to make a character unique. Consider the following to include: - Name

- Motivation

- Relationship to the plot or the main protagonist

- Details relevant to the plot

Tips

- All characters are somehow "derived" from other characters. Think about which two fictional characters could be your new character's parents if you get stuck.

- Include anything you can in the description, including links to articles or music that the character might like.

- Read ancient legends in search of interesting meanings of names.