Content

- Steps

- Part 1 of 2: Conducting Experiments

- Part 2 of 2: Determination of Essential Minerals

- Tips

- Warnings

- What do you need

There are so many minerals - perhaps partly for this reason, they are so interesting to collect. On this page you will find a description of experiments that can be carried out without special equipment and thus significantly narrow the search area, as well as a description of the most common minerals, which can be compared with the results of the experiments.You can even go to the descriptions section right now - maybe you will immediately, without any experience, be able to find the answer to your question. For example, in this section, you will learn how to distinguish real gold from other shiny yellow minerals, read about streaks of shiny colored interlayers in rock, or learn to identify what strange mineral it is that delaminates into plates when rubbed.

Steps

Part 1 of 2: Conducting Experiments

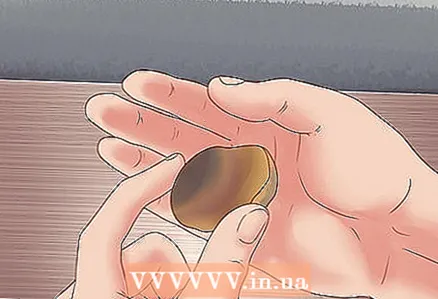

1 First, let's understand the difference between minerals and regular stones. A mineral is a natural combination of chemical elements that forms a specific structure. And, despite the fact that you can find the same mineral in different shapes and colors, it will still show the same properties when tested. In contrast, stones can be composed of a combination of minerals and do not have a crystal lattice. It is not always easy to distinguish between them, however, if the conducted experiment gives different results from different sides of the object, then the object is most likely a stone.

1 First, let's understand the difference between minerals and regular stones. A mineral is a natural combination of chemical elements that forms a specific structure. And, despite the fact that you can find the same mineral in different shapes and colors, it will still show the same properties when tested. In contrast, stones can be composed of a combination of minerals and do not have a crystal lattice. It is not always easy to distinguish between them, however, if the conducted experiment gives different results from different sides of the object, then the object is most likely a stone. - You can try to determine what kind of stone it is, or at least determine which of the three types of rock it belongs to.

2 Learn to navigate the classification of minerals. Thousands of minerals have found a place on our planet, but many of them are classified as rare, or lie too deep underground. Sometimes a couple of experiments are enough, and you have no doubt that this is one of the common minerals from the list in the next section. If your mineral does not fit any of the descriptions above, try checking the mineral classifier for your region. If you have done a lot of experiments, but failed to reduce the number of options to two or three, search the Internet. Look at pictures of every mineral that is similar to yours, and look for all possible recommendations on how to distinguish between these minerals.

2 Learn to navigate the classification of minerals. Thousands of minerals have found a place on our planet, but many of them are classified as rare, or lie too deep underground. Sometimes a couple of experiments are enough, and you have no doubt that this is one of the common minerals from the list in the next section. If your mineral does not fit any of the descriptions above, try checking the mineral classifier for your region. If you have done a lot of experiments, but failed to reduce the number of options to two or three, search the Internet. Look at pictures of every mineral that is similar to yours, and look for all possible recommendations on how to distinguish between these minerals. - It is best to include at least one test that requires exposure to the mineral, such as a hardness test or a streak test. Experiments that involve only viewing and describing can be biased, as different people describe the same mineral in different ways.

3 Examine the shape and surface of the mineral. The totality of the forms of each mineral and the characteristics of the group of minerals are called the "general form". Geologists have many technical terms to describe these characteristics, but usually a general description is sufficient. For example, is your mineral bumpy, rough, or smooth? Is it a mixture of rectangular crystals, or is your specimen bristling with sharp crystal peaks?

3 Examine the shape and surface of the mineral. The totality of the forms of each mineral and the characteristics of the group of minerals are called the "general form". Geologists have many technical terms to describe these characteristics, but usually a general description is sufficient. For example, is your mineral bumpy, rough, or smooth? Is it a mixture of rectangular crystals, or is your specimen bristling with sharp crystal peaks?  4 Take a closer look at how your mineral glistens. Luster refers to how a mineral reflects light, and while not a scientific test, it can be useful to describe. Most minerals have a "glassy" ("glossy") or metallic luster. However, you can describe the shine as either “bold”, “pearlescent” (whitish sheen), “matte” (dull like unglazed ceramics), or whatever definition you think is accurate. ...

4 Take a closer look at how your mineral glistens. Luster refers to how a mineral reflects light, and while not a scientific test, it can be useful to describe. Most minerals have a "glassy" ("glossy") or metallic luster. However, you can describe the shine as either “bold”, “pearlescent” (whitish sheen), “matte” (dull like unglazed ceramics), or whatever definition you think is accurate. ...  5 Pay attention to the color of the mineral. Most people do not see any difficulty in this, but, meanwhile, this experience may turn out to be useless. Small foreign inclusions can cause discoloration, which is why you can find the same mineral in different colors. However, if the mineral has an unusual color, say purple, this can significantly narrow the search area.

5 Pay attention to the color of the mineral. Most people do not see any difficulty in this, but, meanwhile, this experience may turn out to be useless. Small foreign inclusions can cause discoloration, which is why you can find the same mineral in different colors. However, if the mineral has an unusual color, say purple, this can significantly narrow the search area. - When describing minerals, avoid fancy color names like "salmon" or "pus". Try to get by with just red, black and green.

6 Conduct the experience with a touch. This is a useful and simple test as long as you have a piece of white unglazed china. The reverse side of a tile from a bath or kitchen is perfect; maybe you can buy something suitable from a repair shop.Having become the owner of the coveted piece of porcelain, simply rub the mineral on the tiles and see what color it leaves behind. Often the color of the stroke will differ from the base color of the mineral.

6 Conduct the experience with a touch. This is a useful and simple test as long as you have a piece of white unglazed china. The reverse side of a tile from a bath or kitchen is perfect; maybe you can buy something suitable from a repair shop.Having become the owner of the coveted piece of porcelain, simply rub the mineral on the tiles and see what color it leaves behind. Often the color of the stroke will differ from the base color of the mineral. - Glaze gives porcelain and other types of ceramics a glassy (glossy) sheen.

- Remember that some minerals do not leave a streak, especially hard minerals (as they are harder than a dashed plate).

7 Assess the hardness of the material. To quickly determine the hardness of a material, geologists use the Mohs hardness scale, named after its creator. If the result matches the hardness factor "4", but does not reach "5", then the factor of your mineral is between "4" and "5", you can terminate the experiment. Try to scratch your mineral using the common objects listed below (or minerals from the hardness test kit); start at the bottom scores and, if the test is positive, work your way up the scale to the top scores:

7 Assess the hardness of the material. To quickly determine the hardness of a material, geologists use the Mohs hardness scale, named after its creator. If the result matches the hardness factor "4", but does not reach "5", then the factor of your mineral is between "4" and "5", you can terminate the experiment. Try to scratch your mineral using the common objects listed below (or minerals from the hardness test kit); start at the bottom scores and, if the test is positive, work your way up the scale to the top scores: - 1 - Easy to scratch with a fingernail, oily and soft to the touch (corresponds to a notch with stearite)

- 2 - Can be scratched with a fingernail (plaster)

- 3 - Can be easily cut with a knife or nail, scratched with a coin (calcite, lime spar)

- 4 - Easy to scratch with a knife (fluorspar)

- 5 - Hardly can be scratched with a knife, can be scratched with a piece of glass (apatite)

- 6 - Can be scratched with a file, he himself, with effort, can scratch glass (orthoclase)

- 7 - Can scratch file steel, easily scratches glass (quartz)

- 8 - Scratches quartz (topaz)

- 9 - Scratches almost anything, cuts glass (corundum)

- 10 - Scratches or cuts almost anything (diamond)

8 Break up the mineral and study into what pieces it breaks down. Due to the fact that each mineral has a certain structure, then it must disintegrate into parts in a certain way. If in faults of one rock you observe more flat surfaces, then we are dealing with cleavage... If there are no flat surfaces, but continuous chaotic bends and bulges are observed, then a fracture is present in the mineral.

8 Break up the mineral and study into what pieces it breaks down. Due to the fact that each mineral has a certain structure, then it must disintegrate into parts in a certain way. If in faults of one rock you observe more flat surfaces, then we are dealing with cleavage... If there are no flat surfaces, but continuous chaotic bends and bulges are observed, then a fracture is present in the mineral. - Cleavage is described in more detail by the number of fractured planes (usually one to four); also takes into account the concept perfect (smooth) or imperfect (rough) surface.

- Fractures are of several types. They are described as splinter (fibrous), sharp and jagged (hooked), bowl-shaped (flaky, cochlea) or none of the above (uneven).

9 If you still haven't identified your mineral, additional tests can be done. There are many other tests at the disposal of geologists for classifying minerals. However, many are simply not useful for identifying the most common species, and many will require special equipment or hazardous materials. Here is a short description of a few experiments that you may need:

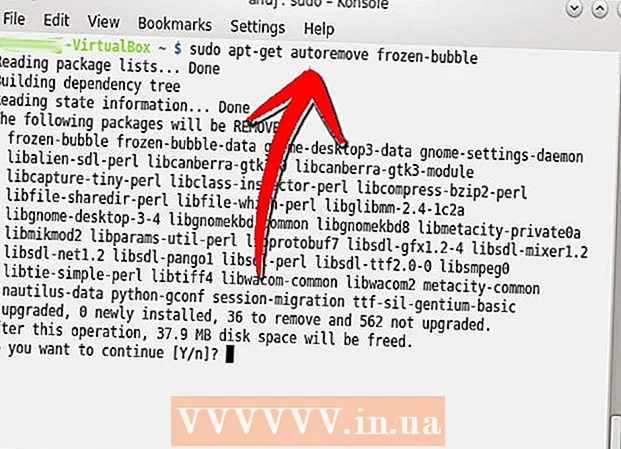

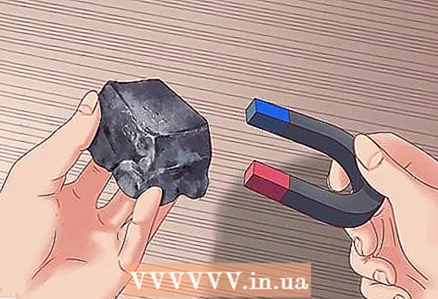

9 If you still haven't identified your mineral, additional tests can be done. There are many other tests at the disposal of geologists for classifying minerals. However, many are simply not useful for identifying the most common species, and many will require special equipment or hazardous materials. Here is a short description of a few experiments that you may need: - If your mineral is attracted by a magnet, then most likely it is magnetite or magnetic iron ore - the only ferromagnet from a number of common minerals. If the attraction is weak or does not meet the definition of magnetite, then your specimen may be pyrrhotite (or magnetic pyrite), franklinite, and ilmenite (or titanium iron ore).

- Some minerals melt easily in a candle or lighter flame, while others will not melt even in a jet flame. Minerals that are easier to melt have a higher fusibility than those that are more difficult to melt.

- If your mineral has a distinctive smell, try to describe it and search the net for minerals with a similar smell. Strong-smelling minerals are not common, however, the presence of bright yellow mineral sulfur can trigger the familiar rotten egg smell.

Part 2 of 2: Determination of Essential Minerals

1 If you are confused about any of the following descriptions, see the previous section. The descriptions below contain terms and numbers from the traditional classification of minerals, such as shape, hardness, fracture appearance, or other definitions. If you are not sure exactly what they mean, refer to the previous section on conducting experiments.

1 If you are confused about any of the following descriptions, see the previous section. The descriptions below contain terms and numbers from the traditional classification of minerals, such as shape, hardness, fracture appearance, or other definitions. If you are not sure exactly what they mean, refer to the previous section on conducting experiments.  2 Crystalline minerals are most often represented by quartz. Quartz is extremely widespread. The crystal's bright luster and beautiful appearance attracts many collectors. On the Mohs scale, quartz has a hardness factor of 7, and if broken, you can see any kind of fracture, but never the flat surface characteristic of cleavage. It leaves no streak on white porcelain. Its luster is glassy.

2 Crystalline minerals are most often represented by quartz. Quartz is extremely widespread. The crystal's bright luster and beautiful appearance attracts many collectors. On the Mohs scale, quartz has a hardness factor of 7, and if broken, you can see any kind of fracture, but never the flat surface characteristic of cleavage. It leaves no streak on white porcelain. Its luster is glassy. - '' '' Milky quartz is a translucent mineral, rose quartz is pink, and amethyst is purple.

3 A hard, glassy mineral without crystals can be another type of quartz, flint or hornfels. Absolutely all quartz has a crystalline structure, however, some varieties, called "cryptocrystalline", consist of microscopic crystals that are not visible to the eye. If you have a mineral with a hardness factor of 7, with a break and with a glassy luster, then it is quite possible that this is a type of quartz called flint. The most common flint is brown or gray.

3 A hard, glassy mineral without crystals can be another type of quartz, flint or hornfels. Absolutely all quartz has a crystalline structure, however, some varieties, called "cryptocrystalline", consist of microscopic crystals that are not visible to the eye. If you have a mineral with a hardness factor of 7, with a break and with a glassy luster, then it is quite possible that this is a type of quartz called flint. The most common flint is brown or gray. - One of the varieties of flint is chalcedony flint or, as it is also called, the chalcedony variety of quartz. However, it is classified in different ways. For example, some consider any black flint to be chalcedony flint, while others will only agree with the definition of chalcedony flint if it has the right luster and is found in a particular rock.

4 The striped minerals are usually chalcedony. Chalcedony is a mixture of quartz with another mineral, morganite. There are many beautiful varieties with different colored stripes. The two most common are:

4 The striped minerals are usually chalcedony. Chalcedony is a mixture of quartz with another mineral, morganite. There are many beautiful varieties with different colored stripes. The two most common are: - Onyx is a type of chalcedony with parallel stripes. Most often it is black or white, but onyxes are also found in other colors.

- Agate has more curved or swirl-forming stripes, and agates come in all sorts of colors. Agate is formed from quartz, chalcedony, or similar minerals.

5 Check if your mineral matches the characteristics of feldspar. Feldspar is the second most widespread after all types of quartz. The hardness factor of this mineral is 6, it leaves a white streak; you can find feldspar of various colors and gloss. When fractured, it forms two flat cleats, the smooth surfaces of which are located almost at right angles to each other.

5 Check if your mineral matches the characteristics of feldspar. Feldspar is the second most widespread after all types of quartz. The hardness factor of this mineral is 6, it leaves a white streak; you can find feldspar of various colors and gloss. When fractured, it forms two flat cleats, the smooth surfaces of which are located almost at right angles to each other.  6 If the mineral comes off in layers during friction, it is probably mica. This mineral is easy to identify, because if you scratch it with your fingernail or even just with your finger, it exfoliates into thin plates. Potassium "(or white) mica pale brown or colorless, whereas magnesian ”(or black) mica is dark brown or black, with gray-brown veins.

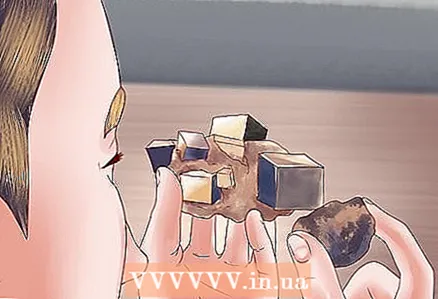

6 If the mineral comes off in layers during friction, it is probably mica. This mineral is easy to identify, because if you scratch it with your fingernail or even just with your finger, it exfoliates into thin plates. Potassium "(or white) mica pale brown or colorless, whereas magnesian ”(or black) mica is dark brown or black, with gray-brown veins.  7 Now let's understand the difference between gold and "cat" gold.Pyritealso known as cat gold, also looks like a shiny yellow metal, but a couple of experiments are enough to make the difference obvious. The hardness factor of pyrite reaches, and sometimes exceeds 6, gold, in turn, is much softer, its value fluctuates between 2 and 3. It leaves a greenish-black streak and can crumble with sufficient pressure.

7 Now let's understand the difference between gold and "cat" gold.Pyritealso known as cat gold, also looks like a shiny yellow metal, but a couple of experiments are enough to make the difference obvious. The hardness factor of pyrite reaches, and sometimes exceeds 6, gold, in turn, is much softer, its value fluctuates between 2 and 3. It leaves a greenish-black streak and can crumble with sufficient pressure. - Marcasite (or radiant pyrite) is another common mineral close to pyrite. But, if the crystals of pyrite have a cubic shape, then marcasite forms needles.

8 Green or blue minerals are most often malachite or azurite. In addition to other minerals, they contain copper. It is she who gives malachite its rich green color, and azurite makes it bright blue.Both minerals often occur together and both have a hardness factor between 3 and 4.

8 Green or blue minerals are most often malachite or azurite. In addition to other minerals, they contain copper. It is she who gives malachite its rich green color, and azurite makes it bright blue.Both minerals often occur together and both have a hardness factor between 3 and 4.  9 Use a mineral classifier or website to identify other species. A mineral classifier for your area will give you all the information you need about the minerals found in your area. If you do have difficulty identifying your specimen, several online resources such as minerals.net will allow you to compare test results with existing benchmarks and thus find the right mineral.

9 Use a mineral classifier or website to identify other species. A mineral classifier for your area will give you all the information you need about the minerals found in your area. If you do have difficulty identifying your specimen, several online resources such as minerals.net will allow you to compare test results with existing benchmarks and thus find the right mineral.

Tips

- Organizing the process is easy: make a list of minerals with characteristics that match those you already established for your mineral. As you learn something new about your mineral, cross out those that no longer fit. And, hopefully, in the end, only one will remain on the list - it will be your desired mineral.

Warnings

- The experiment with hydroiodic acid, which was not presented here, makes sense only in a limited number of cases. The acid can cause serious damage to the skin and eyes, so only carry out this test with protective equipment and an adult.

What do you need

- Unglazed Porcelain Tile (Line Plate)

- Magnet (at your discretion)

To determine hardness:

- coin

- soldering iron / steel for soldering irons

- iron nail

- Mineral classification brochure or website (if your mineral is not described on this page)