Author:

Tamara Smith

Date Of Creation:

24 January 2021

Update Date:

1 July 2024

Content

- To step

- Method 1 of 6: Start an argumentative paragraph

- Method 2 of 6: Start an introductory paragraph

- Method 3 of 6: Start a concluding paragraph

- Method 4 of 6: Start a paragraph of a story

- Method 5 of 6: Using transitions between paragraphs

- Method 6 of 6: Avoid writer's block

- Tips

- Warnings

A paragraph is a small writing unit consisting of several (usually 3-8) sentences. These phrases are all related to a common theme or idea. There are many different types of paragraphs. Some paragraphs make argumentative claims, and others can tell a fictional story. No matter what kind of paragraph you write, you can get started by organizing your thoughts, keeping your reader in mind, and planning carefully.

To step

Method 1 of 6: Start an argumentative paragraph

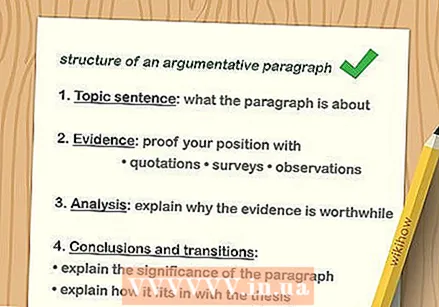

Recognize the structure of an argumentative paragraph. Most argumentative paragraphs have a clearly defined structure, especially in an academic context. Each paragraph helps to support the overarching thesis (or argumentative claim) of the article, and each paragraph contains new information that can convince a reader that your statement is correct. The components that make up a paragraph are the following:

Recognize the structure of an argumentative paragraph. Most argumentative paragraphs have a clearly defined structure, especially in an academic context. Each paragraph helps to support the overarching thesis (or argumentative claim) of the article, and each paragraph contains new information that can convince a reader that your statement is correct. The components that make up a paragraph are the following: - Subject phrase. A topic sentence explains to the reader what the paragraph is about. It usually refers back to the bigger argument somehow and explains why the paragraph belongs in the essay. Sometimes a topic sentence is 2 or even 3 sentences long, although it is usually just a single sentence.

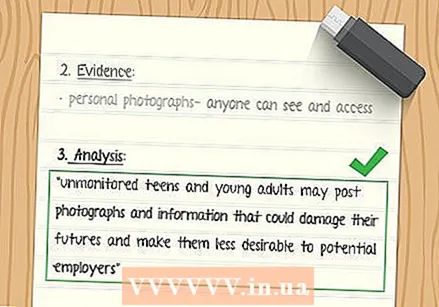

- Evidence. Most of the main paragraphs in an argumentative text contain some sort of proof that your statement is correct. This evidence can be anything: quotes, surveys, or even your own observations. In your paragraphs, this evidence can be presented in a compelling way.

- Analysis. A good paragraph does not only provide evidence. It also takes some time to explain why the evidence is worthwhile, what it means, and why it is better than other pieces of evidence out there. This is where your own analysis comes into play.

- Conclusions and Transitions. After the analysis, a good paragraph will be concluded by explaining why the paragraph is significant, how it ties in with the essay's thesis, and the next paragraph will be introduced.

Read your main thesis again. When writing an argumentative essay, each paragraph should help substantiate your overarching claim. Before you can write an argumentative paragraph, you need to have your main thesis in mind. A main thesis is a 1-3 sentence description of what you are arguing and why it is important. Are you claiming that all Americans should use energy efficient light bulbs at home? Or do you argue that all citizens should be free to choose which products they buy? Before you start writing, make sure you have a good idea of your argument.

Read your main thesis again. When writing an argumentative essay, each paragraph should help substantiate your overarching claim. Before you can write an argumentative paragraph, you need to have your main thesis in mind. A main thesis is a 1-3 sentence description of what you are arguing and why it is important. Are you claiming that all Americans should use energy efficient light bulbs at home? Or do you argue that all citizens should be free to choose which products they buy? Before you start writing, make sure you have a good idea of your argument.  Write the proof and analysis first. It is often easier to start writing in the middle of an argumentative paragraph rather than at the beginning of the paragraph. If you are concerned about the beginning of a paragraph, resolve to focus on the part of the paragraph that is easiest to write: the evidence and analysis. After you have written the simpler part of a paragraph, you can move on to the topic sentence.

Write the proof and analysis first. It is often easier to start writing in the middle of an argumentative paragraph rather than at the beginning of the paragraph. If you are concerned about the beginning of a paragraph, resolve to focus on the part of the paragraph that is easiest to write: the evidence and analysis. After you have written the simpler part of a paragraph, you can move on to the topic sentence.  List all the evidence supporting your main thesis. Regardless of the type of argument you make, you will have to use evidence to convince your reader that you are right. Your evidence can be many things: historical documentation, expert quotes, results of a scientific study, a survey, or your own observations. Before proceeding with your paragraph, read any evidence that you believe supports your claim.

List all the evidence supporting your main thesis. Regardless of the type of argument you make, you will have to use evidence to convince your reader that you are right. Your evidence can be many things: historical documentation, expert quotes, results of a scientific study, a survey, or your own observations. Before proceeding with your paragraph, read any evidence that you believe supports your claim.  Choose 1-3 related pieces of evidence for your paragraph. Each paragraph you write should be coherent and self-contained. This means that you don't have to analyze too many pieces of evidence in each paragraph. Instead, each paragraph should only have 1-3 related pieces of evidence. Carefully review all the evidence you have collected. Are there any pieces of evidence that seem linked together? That's a good indication that they belong in the same paragraph. Some indications that evidence can be linked together include:

Choose 1-3 related pieces of evidence for your paragraph. Each paragraph you write should be coherent and self-contained. This means that you don't have to analyze too many pieces of evidence in each paragraph. Instead, each paragraph should only have 1-3 related pieces of evidence. Carefully review all the evidence you have collected. Are there any pieces of evidence that seem linked together? That's a good indication that they belong in the same paragraph. Some indications that evidence can be linked together include: - If they share common themes or ideas

- If they share a common resource (such as the same document or research)

- If they share a common author

- If they are of the same type of evidence (such as two surveys showing similar results)

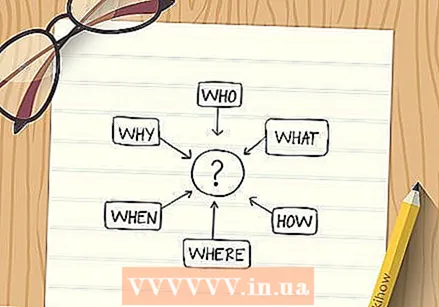

Write about your evidence using the 6 W's. The 6 W's of writing are the "Who", "What", "When", "Where", "Why", and "How". This is the important background information your reader will need to understand the points you are making. As you write down your related evidence, keep your reader in mind. Always explain what your evidence is, how and why it was collected, and what it means. A few special things to keep in mind include:

Write about your evidence using the 6 W's. The 6 W's of writing are the "Who", "What", "When", "Where", "Why", and "How". This is the important background information your reader will need to understand the points you are making. As you write down your related evidence, keep your reader in mind. Always explain what your evidence is, how and why it was collected, and what it means. A few special things to keep in mind include: - You need to define important terms or jargon that your reader may not be familiar with. (What)

- You must provide important dates and locations, if applicable (for example, when a historical document has been signed). (When where)

- You must describe how the evidence was obtained. For example, you could explain the methods of a scientific investigation. (How)

- You must explain who provided you with your evidence. Do you have a quote from an expert? Why is this person considered to be knowledgeable about your topic? (Who)

- You must explain why you think this evidence is important or noteworthy. (Why)

Write 2-3 sentences that analyze your evidence. After you present your main, related piece (s) of evidence, spend some time explaining how you think the evidence is contributing to your larger argument. This is where your own analysis comes into play. You can't simply add evidence and move on: you have to explain its importance. Some questions to ask yourself while analyzing your evidence include:

Write 2-3 sentences that analyze your evidence. After you present your main, related piece (s) of evidence, spend some time explaining how you think the evidence is contributing to your larger argument. This is where your own analysis comes into play. You can't simply add evidence and move on: you have to explain its importance. Some questions to ask yourself while analyzing your evidence include: - What is it that binds this evidence together?

- How does this evidence help prove my main thesis?

- Are there any counter arguments or alternative explanations I should keep in mind?

- What does this evidence reveal? Is there anything special or interesting about it?

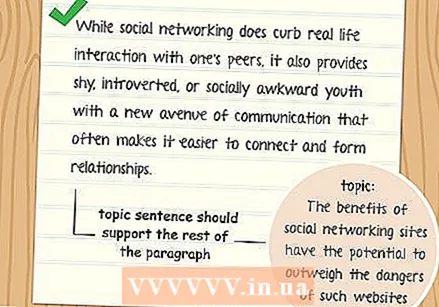

Write your topic sentence. The topic sentence of each paragraph is a signpost that the reader will use to follow your argument. Your introduction will contain your main thesis and each paragraph will build on this main thesis by providing evidence. As the reader reads your text, they will recognize how each paragraph contributes to the main thesis. Remember that the main thesis is the bigger argument and the topic sentence helps prove the main thesis by focusing on a smaller topic or idea. This topic sentence will make a claim or argument, which is then defended or reinforced in the following sentences.Identify the main idea of your paragraph and write a mini statement stating this main idea. Let's say your main thesis is, "Charlie Brown is America's most important comic book character," your essay may contain the following topic sentences:

Write your topic sentence. The topic sentence of each paragraph is a signpost that the reader will use to follow your argument. Your introduction will contain your main thesis and each paragraph will build on this main thesis by providing evidence. As the reader reads your text, they will recognize how each paragraph contributes to the main thesis. Remember that the main thesis is the bigger argument and the topic sentence helps prove the main thesis by focusing on a smaller topic or idea. This topic sentence will make a claim or argument, which is then defended or reinforced in the following sentences.Identify the main idea of your paragraph and write a mini statement stating this main idea. Let's say your main thesis is, "Charlie Brown is America's most important comic book character," your essay may contain the following topic sentences: - "The high ratings that Charlie Brown television specials have garnered for decades demonstrate the influence of this character."

- "Some people argue that superheroes like Superman are more important than Charlie Brown. However, studies show that most Americans identify more quickly with the hapless Charlie than with the powerful, alien Superman."

- "Media historians point to Charlie Brown's striking lyrics, distinctive looks and wisdom as reasons why this character is loved by adults and children."

Make sure the topic sentence supports the rest of the paragraph. After you write your topic sentence, reread your evidence and analysis. Ask yourself if the topic sentence supports the ideas and details of the paragraph. Do they match? Are there any ideas that seem out of place? If so, think about how you can change the topic sentence to cover all the ideas in the paragraph.

Make sure the topic sentence supports the rest of the paragraph. After you write your topic sentence, reread your evidence and analysis. Ask yourself if the topic sentence supports the ideas and details of the paragraph. Do they match? Are there any ideas that seem out of place? If so, think about how you can change the topic sentence to cover all the ideas in the paragraph. - If there are too many ideas, you may have to split the paragraph into two separate paragraphs.

- Make sure your topic sentence isn't simply a restatement of the main thesis itself. Each paragraph should have a clear, unique topic sentence. If you simply say "Charlie Brown is important" at the beginning of each body paragraph, you need to refine your topic sentences more thoroughly.

Close your paragraph. Unlike full essays, not every paragraph will have a full conclusion. However, it can be effective to dedicate a sentence to tying the loose ends of your paragraph and highlight how your paragraph just contributed to your main thesis. You want to do this efficiently and quickly. Write a final sentence that reinforces your argument before moving on to the next set of ideas. Some key words and phrases you can use in a closing sentence are "Therefore", "Ultimately", "As You Can See" and "Thus".

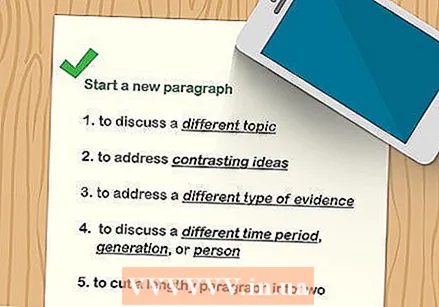

Close your paragraph. Unlike full essays, not every paragraph will have a full conclusion. However, it can be effective to dedicate a sentence to tying the loose ends of your paragraph and highlight how your paragraph just contributed to your main thesis. You want to do this efficiently and quickly. Write a final sentence that reinforces your argument before moving on to the next set of ideas. Some key words and phrases you can use in a closing sentence are "Therefore", "Ultimately", "As You Can See" and "Thus".  When you move on to a new idea, start a new paragraph. You must start a new paragraph when you move on to a new point or idea. By starting a new paragraph, you indicate to your reader that you are switching in some way. Some pointers that you should start a new paragraph include:

When you move on to a new idea, start a new paragraph. You must start a new paragraph when you move on to a new point or idea. By starting a new paragraph, you indicate to your reader that you are switching in some way. Some pointers that you should start a new paragraph include: - When you start discussing a different theme or topic

- When you start to deal with contrasting ideas or counter arguments

- When dealing with a different type of evidence

- When discussing another period, generation or person

- When your current paragraph becomes impractical. If you have too many sentences in your paragraph, you may have too many ideas. Split your paragraph in half or edit your writing to make it easier to read.

Method 2 of 6: Start an introductory paragraph

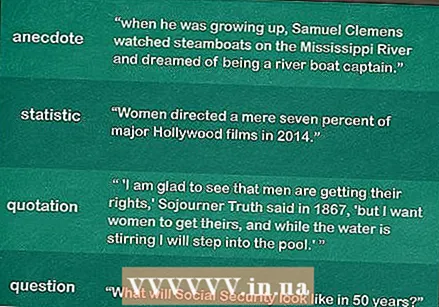

Find a good opening. Start your paper or essay with an interesting sentence that will make the reader want to dive in to read your entire work. There are many ways to choose from. Use humor, surprise, or a clever phrase to get your reader's attention. Look at your research notes to see if any clever phrase, startling statistic, or intriguing anecdote pops out. Some of these options include:

Find a good opening. Start your paper or essay with an interesting sentence that will make the reader want to dive in to read your entire work. There are many ways to choose from. Use humor, surprise, or a clever phrase to get your reader's attention. Look at your research notes to see if any clever phrase, startling statistic, or intriguing anecdote pops out. Some of these options include: - An anecdote: "Growing up, Samuel Clemens watched steamers on the Mississippi River and dreamed of being a riverboat captain."

- A statistic: "Women directed only seven percent of the most important Hollywood movies in 2014."

- A quote: "I'm glad to see men getting their rights," said Sojourner Truth in 1867, "but I want women to get theirs too, and while the water is stirring, I step into the pool."

- A thought-provoking question: "What will Social Security look like in 50 years?"

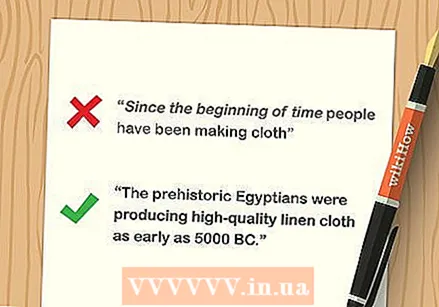

Avoid universal statements. It can be tempting to use a big, general sentence as an opening. However, openings are more effective if they are specific to your topic. Resist the temptation to introduce your essay with phrases such as:

Avoid universal statements. It can be tempting to use a big, general sentence as an opening. However, openings are more effective if they are specific to your topic. Resist the temptation to introduce your essay with phrases such as: - "Since the beginning of time..."

- "From the beginning of humanity..."

- "All men and women ask themselves..."

- "Every human on the planet..."

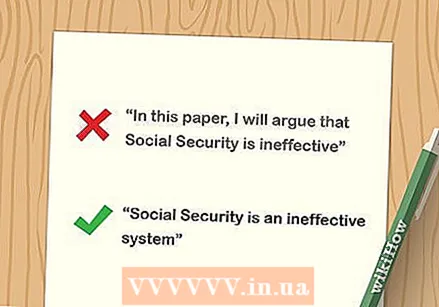

Describe the topic of your essay. Once you have your opening, you will have to write a few sentences to orient your reader to what the rest of your essay will be about. Is your essay an argument about social security? Or is it a history of Sojourner truth? Give your reader a brief roadmap on the scope, purpose, and general thrust of your essay.

Describe the topic of your essay. Once you have your opening, you will have to write a few sentences to orient your reader to what the rest of your essay will be about. Is your essay an argument about social security? Or is it a history of Sojourner truth? Give your reader a brief roadmap on the scope, purpose, and general thrust of your essay. - If possible, avoid expressions such as "In this article I will argue that Social Security is ineffective" or "This document focuses on the ineffectiveness of Social Security." Instead, simply state, "Social security is an ineffective system."

Write sharp, clear sentences. If you want to grab the reader, you need a sentence that is clear and easy to follow. The beginning of your report is not the place to write a complicated, long-winded sentence that stumbles the reader. Use plain words (no jargon), short explanatory sentences, and easy-to-follow logic to guide your introduction.

Write sharp, clear sentences. If you want to grab the reader, you need a sentence that is clear and easy to follow. The beginning of your report is not the place to write a complicated, long-winded sentence that stumbles the reader. Use plain words (no jargon), short explanatory sentences, and easy-to-follow logic to guide your introduction. - Read your paragraph aloud to see if your sentences are clear and easy to follow. If you need to breathe a lot while reading, or if you have trouble keeping up with your ideas out loud, you should shorten your sentences.

Conclude introductory paragraphs of argumentative essays with a main thesis. A main thesis is a 1-3 sentence description of the overarching argument of your essay. If you are writing an argumentative essay, the main thesis is the most important part of your essay. Often times, your main thesis changes slightly as you write your essay. Remember that a main theorem must be:

Conclude introductory paragraphs of argumentative essays with a main thesis. A main thesis is a 1-3 sentence description of the overarching argument of your essay. If you are writing an argumentative essay, the main thesis is the most important part of your essay. Often times, your main thesis changes slightly as you write your essay. Remember that a main theorem must be: - Argumentative. You cannot simply say something that is common knowledge or fact. "Ducks are birds" is not a main thesis.

- Convincingly. Your main thesis must be based on evidence and careful analysis. Do not write a wild, deliberately unconventional, or unprovable statement. Follow where your evidence takes you.

- Suitable for your assignment. Don't forget to adhere to all parameters and guidelines of your assignment.

- Feasible in the allocated space. Keep your statement narrow and focused. That way you can prove your point within the designated space. Do not make a statement that is too broad ("I discovered a new reason why World War II happened") or too narrow ("I will argue that left-handed soldiers wear their coats differently than right-handed soldiers").

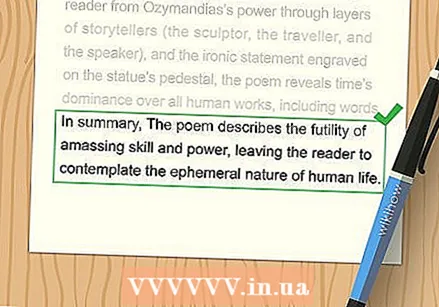

Method 3 of 6: Start a concluding paragraph

Link your conclusion to your introduction. Take the reader back to your introduction by starting the conclusion with a reminder of how the report began. This strategy acts as a framework that keeps your report in book form.

Link your conclusion to your introduction. Take the reader back to your introduction by starting the conclusion with a reminder of how the report began. This strategy acts as a framework that keeps your report in book form. - For example, if you started your article with a quote from the Sojourner truth, you might start the conclusion with, "Although the Sojourner truth spoke nearly 150 years ago, its statement remains true today."

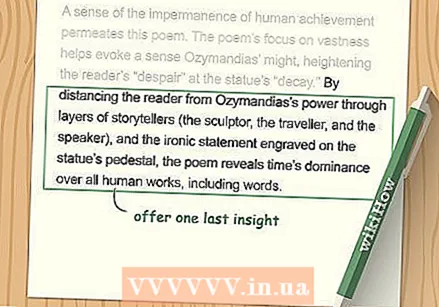

Make one final point. You can use this last section to provide one last insight into the discussion that took place throughout the rest of your report. Use this space to ask a final question or suggest an action item.

Make one final point. You can use this last section to provide one last insight into the discussion that took place throughout the rest of your report. Use this space to ask a final question or suggest an action item. - For example, you can write, "Is an e-cigarette really different from a regular cigarette?"

Summarize your report. If you have written a report that is long and complex, you can choose to keep your conclusion before recapitulating what you have written. This allows you to repeat the most important points for the reader. This also helps the reader to understand how your report is put together.

Summarize your report. If you have written a report that is long and complex, you can choose to keep your conclusion before recapitulating what you have written. This allows you to repeat the most important points for the reader. This also helps the reader to understand how your report is put together. - You can start by writing: "In short, the European Union's cultural policy supports world trade in three ways."

Consider what other work can be done. Conclusions are a great place to be imaginative and think about the bigger picture. Has your essay freed up room for more work? Have you asked some big questions for others to answer? Think of some of the larger ramifications of your essay and articulate them in your conclusion.

Consider what other work can be done. Conclusions are a great place to be imaginative and think about the bigger picture. Has your essay freed up room for more work? Have you asked some big questions for others to answer? Think of some of the larger ramifications of your essay and articulate them in your conclusion.

Method 4 of 6: Start a paragraph of a story

Determine the 6 W's of your story. The 6 W's are Who, What, When, Where, Why and How. If you are writing a creative fictional story, you should answer these questions correctly before you start writing. Not every W should be covered in every paragraph. However, you shouldn't start writing unless you have a good idea of who your characters are, what they do, when and where they do it, and why it's important.

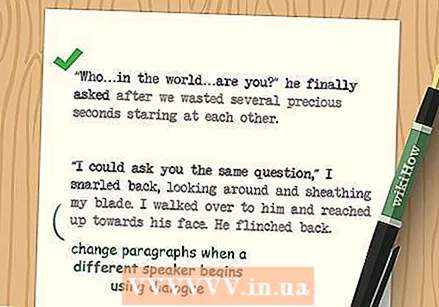

Determine the 6 W's of your story. The 6 W's are Who, What, When, Where, Why and How. If you are writing a creative fictional story, you should answer these questions correctly before you start writing. Not every W should be covered in every paragraph. However, you shouldn't start writing unless you have a good idea of who your characters are, what they do, when and where they do it, and why it's important.  Start a new paragraph when you switch from one W to another. Paragraphs in creative texts are more flexible than paragraphs in argumentative academic essays. A good rule of thumb, however, is that you should start a new paragraph when you switch between the main W's of writing. For example, if you move from one place to another, you start a new paragraph. When you describe another character, you start a new paragraph. When you describe a flashback, you start a new paragraph. This will help keep your reader focused.

Start a new paragraph when you switch from one W to another. Paragraphs in creative texts are more flexible than paragraphs in argumentative academic essays. A good rule of thumb, however, is that you should start a new paragraph when you switch between the main W's of writing. For example, if you move from one place to another, you start a new paragraph. When you describe another character, you start a new paragraph. When you describe a flashback, you start a new paragraph. This will help keep your reader focused. - Always start a new paragraph when another speaker starts using the dialogue. If two characters use the dialogue in the same paragraph, it will create confusion for your reader.

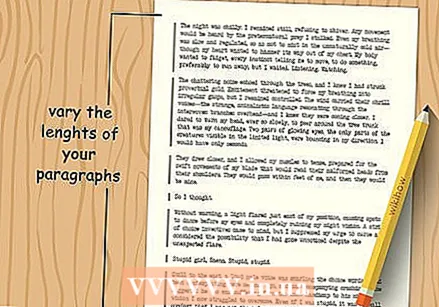

Use paragraphs of different lengths. In academic writing, paragraphs are often about the same length. In creative writing, your paragraphs can be from one word to several hundred words. Carefully consider the effect you want to create with your paragraph so that you can determine the length of your paragraph. By varying the length of your paragraphs you can make your text more interesting to your reader.

Use paragraphs of different lengths. In academic writing, paragraphs are often about the same length. In creative writing, your paragraphs can be from one word to several hundred words. Carefully consider the effect you want to create with your paragraph so that you can determine the length of your paragraph. By varying the length of your paragraphs you can make your text more interesting to your reader. - Longer paragraphs can help create a solid, nuanced description of a person, place, or object.

- Shorter paragraphs can be good for humor, shock, or quick action and dialogue.

Consider the purpose of your paragraph. Unlike an argumentative paragraph, your creative paragraph does not continue with a main thesis. However, it should still serve a purpose. You don't want your paragraph to seem pointless or muddled. Ask yourself what you want your reader to get out of this paragraph. Your paragraph may be:

Consider the purpose of your paragraph. Unlike an argumentative paragraph, your creative paragraph does not continue with a main thesis. However, it should still serve a purpose. You don't want your paragraph to seem pointless or muddled. Ask yourself what you want your reader to get out of this paragraph. Your paragraph may be: - Provide your reader with important background information

- Improve the plot of your story

- Show how your characters relate to each other

- Describe the setting of your story

- Explain a character's motives

- Provide an emotional response from your reader, such as fear, laughter, fear, or sentiment.

Use writing exercises to get ideas. Sometimes you have to work and plan for a while before you can write an effective sentence. Writing practice is a great tool for getting to know the story you want to write. These exercises can also help you view your story from new angles and perspectives. Some exercises to help you get inspiration for your paragraph include:

Use writing exercises to get ideas. Sometimes you have to work and plan for a while before you can write an effective sentence. Writing practice is a great tool for getting to know the story you want to write. These exercises can also help you view your story from new angles and perspectives. Some exercises to help you get inspiration for your paragraph include: - Write a letter from one character to another

- Write a few pages of a journal from your character's perspective

- Read about the time and place where your story is set. Which historical details are of most interest to you?

- Write a timeline of plot events to keep you up to date

- Do a "creative writing" exercise, spending 15 minutes writing anything you can think of about your story. You can figure it out and organize it later.

Method 5 of 6: Using transitions between paragraphs

Connect the new paragraph with the previous one. When you move to a new paragraph in your text, each will serve a specific purpose. Begin each new paragraph with a topic sentence that clearly builds on your previous thought.

Connect the new paragraph with the previous one. When you move to a new paragraph in your text, each will serve a specific purpose. Begin each new paragraph with a topic sentence that clearly builds on your previous thought.  Signal a change in time or order. When your paragraphs build up a sequence (such as discussing three different reasons why a war took place), start each paragraph with a word or phrase that tells the reader where you are in the sequence.

Signal a change in time or order. When your paragraphs build up a sequence (such as discussing three different reasons why a war took place), start each paragraph with a word or phrase that tells the reader where you are in the sequence. - For example, you could write, "First ..." The next paragraph would start with "Second ..." The third paragraph might start with "Third ..." or "Finally ..."

- Other words to identify a sequence are: finally, ultimately, first, first, second, or last.

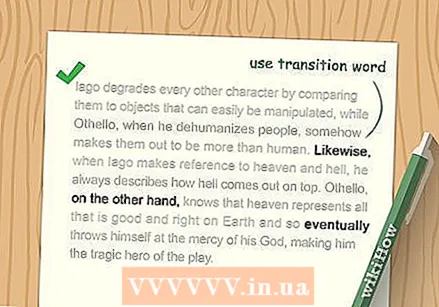

Use a transition word to compare or contrast paragraphs. Use your paragraphs to compare or contrast two ideas. The word or phrase that begins the topic sentence tells the reader to keep the previous paragraph in mind while reading the next paragraph. Then they will follow your comparison.,

Use a transition word to compare or contrast paragraphs. Use your paragraphs to compare or contrast two ideas. The word or phrase that begins the topic sentence tells the reader to keep the previous paragraph in mind while reading the next paragraph. Then they will follow your comparison., - For example, use phrases such as "in comparison" or "similar" to compare.

- However, use phrases such as "despite," "however," or "on the contrary" to indicate that the paragraph will contrast or contradict the idea of the previous paragraph.

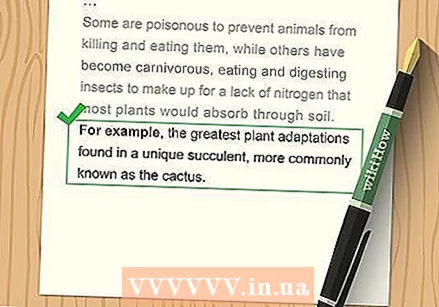

Use a transition phrase to indicate that another example is. If you discussed a particular phenomenon in the previous section, give the reader a good example in the next section. This will be a concrete example that highlights a common phenomenon that you discussed earlier.

Use a transition phrase to indicate that another example is. If you discussed a particular phenomenon in the previous section, give the reader a good example in the next section. This will be a concrete example that highlights a common phenomenon that you discussed earlier. - Use expressions such as "for example", "such as", "so" or "more specific".

- You can also use a transition preview if you place special emphasis on the preview. In this case, use transition words such as "in particular" or "in particular." For example, you might write, "Sojourner Truth, in particular, was an outspoken critic of the patriarchal system of the Reconstruction Age."

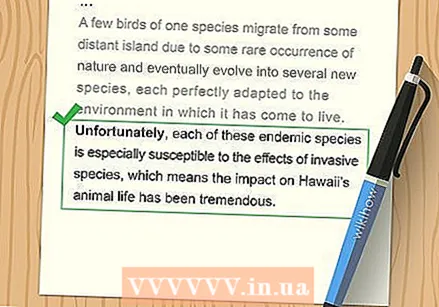

Describe the attitude the reader should associate with something. When describing a situation or phenomenon, you can provide the reader with clues that indicate how this phenomenon should be perceived. Use vivid, descriptive words to guide the reader's opinions and encourage them to see things from your point of view.

Describe the attitude the reader should associate with something. When describing a situation or phenomenon, you can provide the reader with clues that indicate how this phenomenon should be perceived. Use vivid, descriptive words to guide the reader's opinions and encourage them to see things from your point of view. - Words like "happy", "strangely enough" and "unfortunately" are useful here.

Show cause and effect. The connection between one paragraph and the next may be that something in the first paragraph causes something in the second paragraph. This cause and effect are indicated by transition words such as: "correspondingly", "as a result", "thus", "therefore" or "for this reason."

Show cause and effect. The connection between one paragraph and the next may be that something in the first paragraph causes something in the second paragraph. This cause and effect are indicated by transition words such as: "correspondingly", "as a result", "thus", "therefore" or "for this reason."  Follow transition sentences with a comma. Use the correct punctuation in your text by following the sentence with a comma. Most transitional phrases such as "finally", "finally" and "especially" are subjunctive adverbs. These sentences must be separated from the rest of the sentence by a comma.

Follow transition sentences with a comma. Use the correct punctuation in your text by following the sentence with a comma. Most transitional phrases such as "finally", "finally" and "especially" are subjunctive adverbs. These sentences must be separated from the rest of the sentence by a comma. - For example, you can write, "Sojourner Truth was, in particular, an outspoken critic ..."

- "In the end we can see ..."

- And finally, the expert witness claimed...

Method 6 of 6: Avoid writer's block

Do not panic. Most people experience writer's block at some point in their life. Relax and take a deep breath. A few simple tips and tricks can help you get through your anxiety.

Do not panic. Most people experience writer's block at some point in their life. Relax and take a deep breath. A few simple tips and tricks can help you get through your anxiety.  Write freely for 15 minutes. If you're stuck in your paragraph, pause your brain for 15 minutes. Just write down anything you think is important to your topic. What do you care about? What should others care about? Remind yourself of what you find interesting and enjoyable in your paragraph. Just writing for a few minutes - even if you're writing material that won't be included in your final draft - will inspire you to keep going.

Write freely for 15 minutes. If you're stuck in your paragraph, pause your brain for 15 minutes. Just write down anything you think is important to your topic. What do you care about? What should others care about? Remind yourself of what you find interesting and enjoyable in your paragraph. Just writing for a few minutes - even if you're writing material that won't be included in your final draft - will inspire you to keep going.  Choose a different section to write. You don't have to write a story, paper, or paragraph in that order from start to finish. If you are struggling to write your introduction, choose your most interesting editorial to write. You may find it a more manageable task - and you may get ideas for how to write the more difficult sections.

Choose a different section to write. You don't have to write a story, paper, or paragraph in that order from start to finish. If you are struggling to write your introduction, choose your most interesting editorial to write. You may find it a more manageable task - and you may get ideas for how to write the more difficult sections.  Talk about your ideas out loud. If you stumble across a complicated phrase or concept, try to explain it out loud instead of on paper. Talk to your parents or a friend about the concept. How could you explain it to them over the phone? Write it down as soon as you feel comfortable saying it out loud.

Talk about your ideas out loud. If you stumble across a complicated phrase or concept, try to explain it out loud instead of on paper. Talk to your parents or a friend about the concept. How could you explain it to them over the phone? Write it down as soon as you feel comfortable saying it out loud.  Tell yourself that first drafts are not perfect. First drafts are never perfect. You can always resolve imperfections or cluttered sentences in future drafts. Just focus on getting your ideas on paper now and revising later.

Tell yourself that first drafts are not perfect. First drafts are never perfect. You can always resolve imperfections or cluttered sentences in future drafts. Just focus on getting your ideas on paper now and revising later.  Go for a walk. Your brain sometimes needs breaks to function at a high level. If you've been struggling with a paragraph for more than an hour, walk for 20 minutes and come back later. You may find that it looks a lot easier when you've taken a break.

Go for a walk. Your brain sometimes needs breaks to function at a high level. If you've been struggling with a paragraph for more than an hour, walk for 20 minutes and come back later. You may find that it looks a lot easier when you've taken a break.

Tips

- Format paragraphs using indents. Use the "tab" key on your keyboard or indent about an inch and a half if writing by hand. This gives the reader a visual signal that you have started a new paragraph.

- Make sure each paragraph contains a coherent set of ideas. If you find yourself explaining too many concepts, terms, or characters, divide your text into several paragraphs.

- Give yourself plenty of time for revisions. Your first draft of your paragraph may not be perfect. Put your thoughts on paper and structure them later.

Warnings

- Never plagiarize. Cite your sources carefully for your research and don't copy other people's ideas. Plagiarism is a serious infringement of intellectual property and can have serious consequences.