Author:

Charles Brown

Date Of Creation:

5 February 2021

Update Date:

1 July 2024

Content

- To step

- Part 1 of 3: Establishing the big picture

- Part 2 of 3: Filling in the details

- Part 3 of 3: Putting it into practice

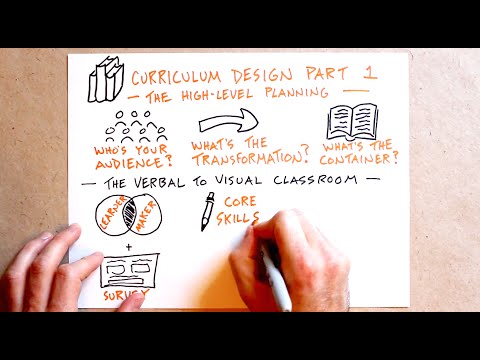

A curriculum is a guide for teachers to teach content and skills. Some curricula are more general guidelines, while others are very detailed and include instructions for day-to-day lessons. Developing a curriculum is quite a challenge, especially when expectations are so broad. Regardless of the situation, it's important to start with a general topic and add more details with each step. Finally, you should evaluate the lesson plan to see if any changes need to be made.

To step

Part 1 of 3: Establishing the big picture

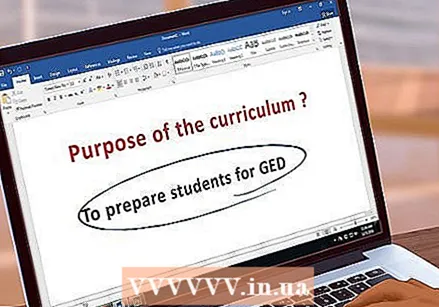

Determine the purpose of the curriculum. Your curriculum should have a clear subject and purpose. The subject should be appropriate for the age of the students and the environment in which the curriculum is taught.

Determine the purpose of the curriculum. Your curriculum should have a clear subject and purpose. The subject should be appropriate for the age of the students and the environment in which the curriculum is taught. - If you are asked to design a course, ask yourself questions about the overall purpose of the course. Why am I teaching this teaching material? What do students measure know? What should they be able to do?

- For example, when developing a summer writing course for high school students, you need to think specifically about what you want the students to learn from the lessons. One goal could be for students to learn how to write a one-act play.

- Even if a topic and course have been assigned to you, you still need to ask these questions so that you have a good understanding of the purpose of the curriculum.

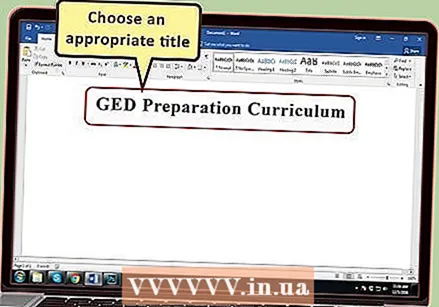

Choose an appropriate title. Depending on the learning objective, the naming of a curriculum can be an uncomplicated process or one that requires more thinking. A curriculum for pre-university students may be called "pre-university preparatory curriculum." A program to support young people with eating disorders may need a more thoughtful title that is attractive to teenagers and meets their needs.

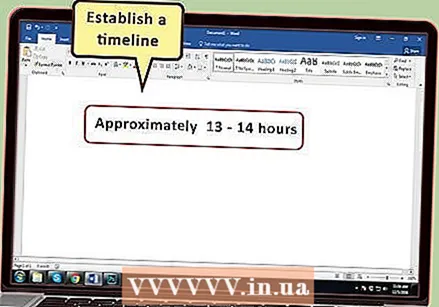

Choose an appropriate title. Depending on the learning objective, the naming of a curriculum can be an uncomplicated process or one that requires more thinking. A curriculum for pre-university students may be called "pre-university preparatory curriculum." A program to support young people with eating disorders may need a more thoughtful title that is attractive to teenagers and meets their needs.  Establish a timeline. Talk to your supervisor about how much time you have to deliver the course. Some courses last a full year and others only one semester. If you teach at a school, try to find out how much time has been allocated to your classes. Once you have a timeline, you can start organizing your curriculum into smaller sections.

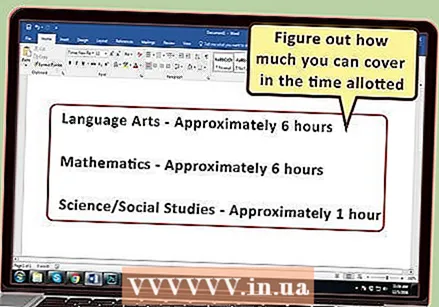

Establish a timeline. Talk to your supervisor about how much time you have to deliver the course. Some courses last a full year and others only one semester. If you teach at a school, try to find out how much time has been allocated to your classes. Once you have a timeline, you can start organizing your curriculum into smaller sections.  Check how much you can teach in the allotted class time. Use your knowledge of your students (age, abilities, etc.) and your knowledge of the curriculum to get an idea of the amount of information you can cover over the time you have been given. You don't need to plan activities yet, but you can start thinking about what's possible.

Check how much you can teach in the allotted class time. Use your knowledge of your students (age, abilities, etc.) and your knowledge of the curriculum to get an idea of the amount of information you can cover over the time you have been given. You don't need to plan activities yet, but you can start thinking about what's possible. - Check how often you will see the students. Classes you teach once or twice a week may have a different outcome than classes you see every day.

- For example, suppose you are compiling a theater curriculum. The difference between a two-hour class once a week for three weeks and a two-hour class every day for three months is significant. In those three weeks it may be possible to create a 10-minute play. Three months, on the other hand, can be enough time for full production.

- This step may not apply to all teachers. High schools often follow government standards that require predefined topics to be addressed throughout the year. Students often take exams or exams at the end of the year, so there is a lot more pressure to meet all standards.

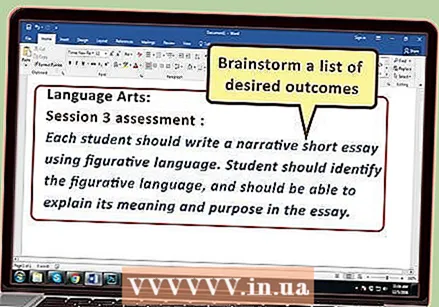

Brainstorm a list of desired results. List the content you want your students to learn and what they should be able to do by the end of the course. It is important to have clear objectives that outline the skills and knowledge your students will acquire. Without these objectives you will not be able to evaluate the students or the effectiveness of the curriculum.

Brainstorm a list of desired results. List the content you want your students to learn and what they should be able to do by the end of the course. It is important to have clear objectives that outline the skills and knowledge your students will acquire. Without these objectives you will not be able to evaluate the students or the effectiveness of the curriculum. - For example, in your summer course on how to write a play, you could teach your students how to write a scene, develop well-rounded characters, and create a storyline.

- Teachers in accredited schools are expected to follow government set standards. Most schools adhere to a government-established curriculum that specifies exactly what students should be able to do at the end of the school year.

Consult existing curricula or curricula for inspiration. Search online for curricula or standards developed in your area. If you work in a school, check with other teachers and supervisors about curricula from previous years. It is much easier to work on your own curriculum from an existing example.

Consult existing curricula or curricula for inspiration. Search online for curricula or standards developed in your area. If you work in a school, check with other teachers and supervisors about curricula from previous years. It is much easier to work on your own curriculum from an existing example. - For example, if you teach drama writing, you can search online for "Playwriting Curriculum" or "Playwriting Lesson Plan".

Part 2 of 3: Filling in the details

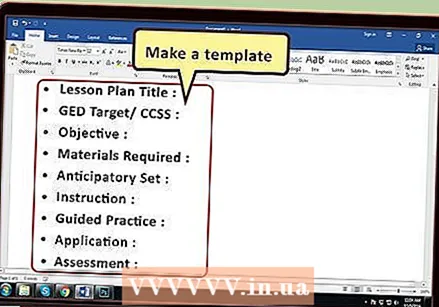

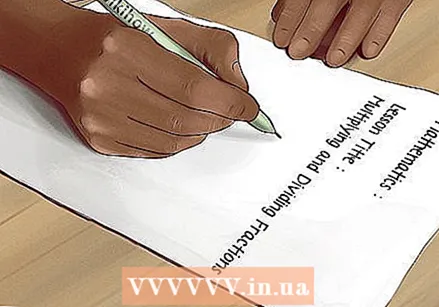

Create a template. Curricula are usually arranged in such a way that there is room for each part. Some institutions ask teachers to use a standardized template, so know what is expected of you. If a template is not provided, search online or create your own. This will help you keep your curriculum organized and presentable.

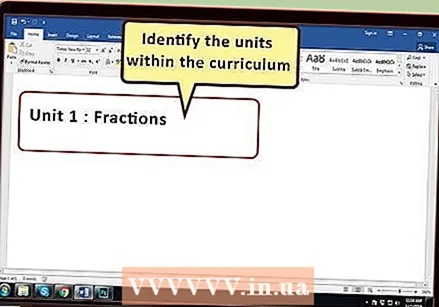

Create a template. Curricula are usually arranged in such a way that there is room for each part. Some institutions ask teachers to use a standardized template, so know what is expected of you. If a template is not provided, search online or create your own. This will help you keep your curriculum organized and presentable.  Determine which units the curriculum will consist of. Units, or themes, are the main topics covered in the curriculum. Organize your brainstorming session or government standards into uniform sections that have a logical order. Units can cover major topics such as love, planets or equations, and major topics such as multiplication or chemical reactions. The number of units varies by curriculum and can last from a week to eight weeks.

Determine which units the curriculum will consist of. Units, or themes, are the main topics covered in the curriculum. Organize your brainstorming session or government standards into uniform sections that have a logical order. Units can cover major topics such as love, planets or equations, and major topics such as multiplication or chemical reactions. The number of units varies by curriculum and can last from a week to eight weeks. - The title of a unit can be a single word or a short sentence. For example, a unit about character development is called "Character Creation."

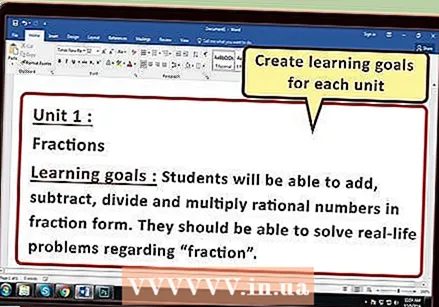

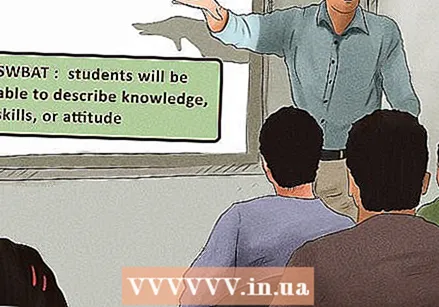

Create learning goals for each unit. Learning objectives are the specific things students need to know and be able to do at the end of the unit. You've thought about this for a while during your first class brainstorming sessions, and now you're getting more specific. As you write the learning goals, ask yourself some important questions.What does the government say is required for students to know? How do I want my students to think about this topic? What skills will my students soon learn? In many cases you can derive your learning goals directly from the general standard.

Create learning goals for each unit. Learning objectives are the specific things students need to know and be able to do at the end of the unit. You've thought about this for a while during your first class brainstorming sessions, and now you're getting more specific. As you write the learning goals, ask yourself some important questions.What does the government say is required for students to know? How do I want my students to think about this topic? What skills will my students soon learn? In many cases you can derive your learning goals directly from the general standard. - Use the acronym SZISO (students are able to…). If you get stuck, start each learning objective with "Students are able to ..." This works for both skills and content knowledge. For example, `` Students are able to produce a two-page analysis of the reasons behind the Civil War. '' This requires that students have gained knowledge (the causes of the American Civil War) and can do something with that knowledge (a written analysis ).

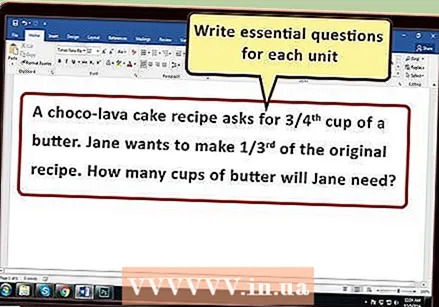

Write essential questions for each unit. Each unit should consist of 2 to 4 general questions to be explored in the unit. Essential questions guide students in understanding the more important parts of the theme. Essential questions are often large, complex questions that cannot always be answered in one lesson.

Write essential questions for each unit. Each unit should consist of 2 to 4 general questions to be explored in the unit. Essential questions guide students in understanding the more important parts of the theme. Essential questions are often large, complex questions that cannot always be answered in one lesson. - For example, an essential question for a high school fraction unit might be, `` Why doesn't division always make things smaller? '' An essential question for a character development unit might be, `` How can a person's decisions and actions reveal his personality? '

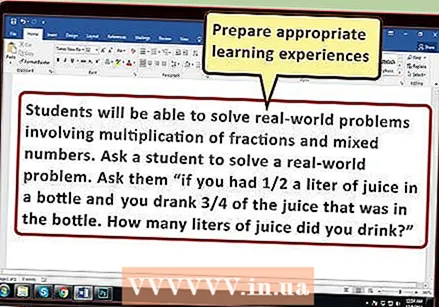

Prepare appropriate learning experiences. Once you have an ordered set of units, you can begin to think about what kind of materials, content, and experiences students need to understand each theme. This can be provided by the textbook to be used, texts to be read, projects, discussions and outings.

Prepare appropriate learning experiences. Once you have an ordered set of units, you can begin to think about what kind of materials, content, and experiences students need to understand each theme. This can be provided by the textbook to be used, texts to be read, projects, discussions and outings. - Consider your audience. Remember that there are many ways to acquire skills and knowledge. Use books, multimedia, and activities that will engage the students you are working with.

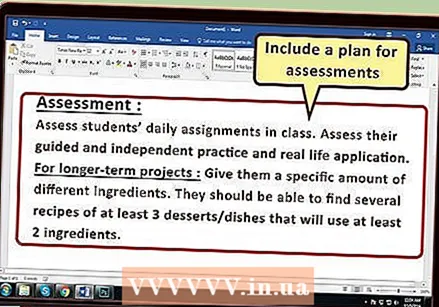

Include a plan for evaluations. Students must be judged on their performance. This helps the student to find out if they were successful in understanding the content, and it helps the teacher to know if he / she was successful in conveying the content. In addition, evaluations help the teacher determine whether changes should be made to the curriculum in the future. There are many ways to assess student performance, and evaluations must be present in every unit.

Include a plan for evaluations. Students must be judged on their performance. This helps the student to find out if they were successful in understanding the content, and it helps the teacher to know if he / she was successful in conveying the content. In addition, evaluations help the teacher determine whether changes should be made to the curriculum in the future. There are many ways to assess student performance, and evaluations must be present in every unit. - Use formative assessments. Formative evaluations are usually smaller, more informal evaluations that provide feedback on the learning process so that you can make changes to the curriculum during the unit. While formative assessments are usually part of the daily lesson plan, they can also be included in the unit descriptions. Examples include journal entries, quizzes, collages, or short written responses.

- Use summative assessments. Summative evaluations occur after a topic has been fully addressed. These assessments are suitable before the end of a unit or at the end of the course. Examples of summative assessments are tests, presentations, performances, essays or portfolios. These evaluations range from discussing specific details to answering essential questions or discussing larger issues.

Part 3 of 3: Putting it into practice

Use the curriculum for lesson planning. Lesson planning is usually separate from the curriculum development process. While many teachers write their own curricula, this is not always the case. Sometimes the person who wrote the curriculum is not the same person who is supposed to teach it. Either way, make sure that what is indicated in the curriculum is used to support lesson planning.

Use the curriculum for lesson planning. Lesson planning is usually separate from the curriculum development process. While many teachers write their own curricula, this is not always the case. Sometimes the person who wrote the curriculum is not the same person who is supposed to teach it. Either way, make sure that what is indicated in the curriculum is used to support lesson planning. - Ensure the transfer of necessary information from your curriculum to your lesson plan. Include the unit name, essential questions, and the purpose of the unit you will be addressing in class.

- Make sure that the objectives of the lesson help students achieve the goals of the unit. Lesson objectives (also called goals, objectives or "SZISO") are similar to the goals of the unit, but more specific. Remember that students must be able to complete the goal at the end of the lesson. For example, "Students Can Explain the Four Causes of the American Civil War" is specific enough to cover in class.

Give and observe the lessons. Once you have developed the curriculum, you must put it into action. You don't know if it works until you try it out with real teachers and real students. Notice how students respond to the topics, teaching methods, assessments, and lessons.

Give and observe the lessons. Once you have developed the curriculum, you must put it into action. You don't know if it works until you try it out with real teachers and real students. Notice how students respond to the topics, teaching methods, assessments, and lessons.  Make adjustments. You can do this during the course or afterwards. Reflect on how the students reacted to the material. Revisions are important, especially as standards, technology, and students are always changing.

Make adjustments. You can do this during the course or afterwards. Reflect on how the students reacted to the material. Revisions are important, especially as standards, technology, and students are always changing. - Ask yourself questions while revising the curriculum. Are the students getting close to the learning goals? Are they able to answer the essential questions? Do students meet the standards? Are students prepared for learning outside of the classroom? If not, you can make corrections to the content, teaching styles and order.

- You can revise every aspect of the curriculum, but everything must be coordinated. Remember that any changes you make to common topics should be reflected in the other topics. For example, if you change the topic of a unit, don't forget to define new essential questions, objectives and evaluations.