Author:

Tamara Smith

Date Of Creation:

22 January 2021

Update Date:

2 July 2024

Content

- To step

- Part 1 of 4: Understanding the structure of haiku

- Part 2 of 4: Determining the subject of the haiku

- Part 3 of 4: Use sensory language

- Part 4 of 4: Become a haiki writer

- Tips

Haiku (俳 句 hai cow) are short poems that use a sensory language to capture a feeling or image. Haiku are usually inspired by an element of nature, a moment of beauty, or a strong experience. This form of poetry was originally developed by Japanese poets and was later adapted by poets from English literature and writers from many other countries. Read on to learn how to write a haiku yourself.

To step

Part 1 of 4: Understanding the structure of haiku

Understanding the sound structure of haiku. The traditional Japanese haiku consists of 17 on, or sounds, divided into three stages: 5 sounds, 7 sounds, and 5 sounds. English and other Western poets interpret these on as syllables. The haiku poetic form has developed considerably over the years and most poets no longer hold to this structure so firmly. Modern haiku can consist of more than 17 sounds, or consist of just one sound.

Understanding the sound structure of haiku. The traditional Japanese haiku consists of 17 on, or sounds, divided into three stages: 5 sounds, 7 sounds, and 5 sounds. English and other Western poets interpret these on as syllables. The haiku poetic form has developed considerably over the years and most poets no longer hold to this structure so firmly. Modern haiku can consist of more than 17 sounds, or consist of just one sound. - While Japanese on are always short, English and other Western syllables can vary considerably in length. This allows a Western haiku of 17 syllables to be many times longer than a traditional Japanese 17-on poem, and thereby misses its mark a bit. The haiku is meant to capture an image with just a few sounds. Although the 5-7-5 structure seems to be no longer mandatory for haiku, children still learn this rule to learn how to write haiku.

- If you are unsure about the number of sounds or syllables to use in your haiku, revert to the Japanese idea that a haiku should be expressed in one breath. In English or Dutch, a haiku will therefore have to cover about 10 to 14 syllables. For example, consider American writer Jack Kerouac's haiku:

- Snow in my shoe

- Abandoned

- Sparrow's nest

- If you are unsure about the number of sounds or syllables to use in your haiku, revert to the Japanese idea that a haiku should be expressed in one breath. In English or Dutch, a haiku will therefore have to cover about 10 to 14 syllables. For example, consider American writer Jack Kerouac's haiku:

Use the haiku to keep two ideas side by side. The Japanese word kiru, meaning to cut, embodies the concept that a haiku should always juxtapose two ideas or notions. These two are grammatically independent, and also differ in imagery.

Use the haiku to keep two ideas side by side. The Japanese word kiru, meaning to cut, embodies the concept that a haiku should always juxtapose two ideas or notions. These two are grammatically independent, and also differ in imagery. - Japanese haiku are usually written on one line, with a kireji (the cutting word), which separates the two contrasting concepts. This one kireji usually appears at the end of one of the sound lines. There is no literal translation for kireji, which is why it is often translated as a dash. The following concept is from haiku grandmaster Matsuo Bashō:

- how cool the feeling of a wall against the feet - siesta

- Western haiku is usually written on three lines. The contrasting ideas (of which there should be only two) are “cut” by a line break, punctuation, or simply some space. This Dutch poem was written by Willem Hussem:

- Drip from

- stresses a water tap

- the silence in the house

- However you shape the haiku, the idea is to jump between the two parts and reinforce the meaning of the poem by making an “internal comparison”. Creating this two-part structure effectively is perhaps the trickiest part of writing haiku. It can be difficult not to make the connection between the two parts too obvious, but you should also be careful that the distance between them is not too great.

- Japanese haiku are usually written on one line, with a kireji (the cutting word), which separates the two contrasting concepts. This one kireji usually appears at the end of one of the sound lines. There is no literal translation for kireji, which is why it is often translated as a dash. The following concept is from haiku grandmaster Matsuo Bashō:

Part 2 of 4: Determining the subject of the haiku

Distilling a poignant experience. Haiku has traditionally focused on details of a person's personal environment and how these relate to the human condition. Think of haiku as a kind of meditation that tries to express an objective image or feeling, without attaching subjective judgment or analysis. If you notice something that you would like to show others, it may be suitable as a subject for a haiku.

Distilling a poignant experience. Haiku has traditionally focused on details of a person's personal environment and how these relate to the human condition. Think of haiku as a kind of meditation that tries to express an objective image or feeling, without attaching subjective judgment or analysis. If you notice something that you would like to show others, it may be suitable as a subject for a haiku. - Japanese poets used haiku to record a fleeting natural phenomenon. This could be like a frog jumping up, rain falling on the leaves, or a flower bending in the wind. Many people take a walk to find new inspiration for their poems. In Japan these walks are called gingko walks.

- Modern haiku can deviate from the traditional natural aspect. Today one can choose to have the city, emotions, relationships, or even humorous occurrences as the subject of a haiku.

- Refer to the season. A reference to the season, or a change of season (in Japanese kigo called) is an essential element of haiku. The reference can be direct, such as inserting a word like “summer” or “spring”, but it can also be more subtle. For example, if you use the flower type "wisteria" in your poem, you are subtly referring to summer because this flower only blooms then.

- Scroll within your topic. In keeping with the idea that the haiku should contain two contrasting ideas, you can choose to shift the perspective on your subject. This creates two parts again. For example, you can choose to focus on a crawling ant on a tree first, and then zoom out until you have a view of the entire forest. This gives the poem a deeper metaphorical meaning than if you were just focusing on the ant. This English-language poem by Richard Wright does this:

- Whitecaps on the bay:

- A broken signboard banging

- In the April wind.

Part 3 of 4: Use sensory language

Describe the details. Haiku consist of details acquired by the five senses. The poet witnesses an event and uses words to express this experience in such a way that others can share it. When you have chosen the subject of your haiku, think about the details you want to describe. Bring the topic to mind and ask yourself the following questions:

Describe the details. Haiku consist of details acquired by the five senses. The poet witnesses an event and uses words to express this experience in such a way that others can share it. When you have chosen the subject of your haiku, think about the details you want to describe. Bring the topic to mind and ask yourself the following questions: - What did you notice about the subject? What colors, textures, and contrasts have you seen?

- How did your topic sound? What was the tenor and volume of the event?

- Did it have a certain smell or taste? Can you describe it accurately?

- Show, instead of telling. Haiku are snapshots of the objective experience, and not of the subjective interpretation or analysis of certain events. It is important to show the reader an absolute truth of the moment, and not to tell him / her what you felt about it. Let the reader feel his or her own emotions in response to the image.

- Opt for restrained and subtle imagery. Do not say it is summer, but describe the angle at which the sun falls, or how the snowflakes are whirling.

- Avoid clichés. Standard phrases like “a dark, stormy night” lose their power over time. Think carefully about the image you want to describe, using imaginative and original language. This doesn't mean grabbing the Van Dale and looking for the most unusual words, just simply describe what you have experienced and express in the fairest possible language you can find.

Part 4 of 4: Become a haiki writer

Get inspired. Go outside for inspiration, as did the great haiku poets. Take a walk and tune in to your surroundings. Which details appeal to you? And why do they do that?

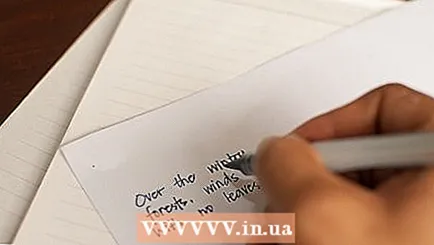

Get inspired. Go outside for inspiration, as did the great haiku poets. Take a walk and tune in to your surroundings. Which details appeal to you? And why do they do that? - Bring a notebook to write lines as soon as they come to mind. You never know when the inspiration will come to you. A stone in a stream, a rat running down the train tracks, you never know.

- Read haiku from other writers. The beauty and simplicity of haiku has inspired thousands of poets in as many languages to write in this form of poetry. Reading other haiku can boost your own imagination.

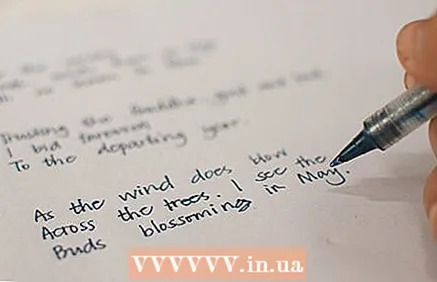

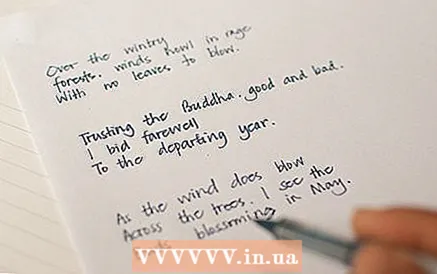

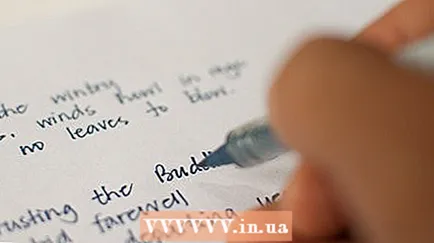

To practise. As with everything else, practice makes perfect. Considered the greatest haiku poet of all time, Bashō said that every haiku must have passed the tongue a thousand times. Write and rewrite each poem until your haiku meaning is perfectly expressed. Realize that you don't necessarily have to stick to the 5-7-5 structure, that every real literary haiku one kigo has, a two-part structure, and primarily objective sensory imagery.

To practise. As with everything else, practice makes perfect. Considered the greatest haiku poet of all time, Bashō said that every haiku must have passed the tongue a thousand times. Write and rewrite each poem until your haiku meaning is perfectly expressed. Realize that you don't necessarily have to stick to the 5-7-5 structure, that every real literary haiku one kigo has, a two-part structure, and primarily objective sensory imagery. - Maintain contact with other poets. If you really want to get serious about haiku, it can pay off to join a haiku organization. Some well-known organizations are the Haiku Society of America, Haiku Canada, the British Haiku Society, but there are similar groups around the world. In the Netherlands, for example, there is the Haiku Circle Netherlands. There are also haiku magazines such as Modern Haiku and Frogpond. By reading this you can learn more about this art form.

Tips

- The haiku is descended from haikai no renga. This is a group poem of usually a hundred stanzas. The hokku, the first stanza, of this renga collaboration, refers to the season and has an intersection. Haiku as an independent art form builds on this tradition

- Haiku is also called “unfinished” poetry, because the reader has to finish it in his / her own heart.

- Unlike traditional Western poems, haiku almost never rhyme.

- Modern haiku poets can write poems that are very short and only contain a few words. Some people also write mini haiku, with a 3-5-3 syllable structure.