Content

Disordered eating is a serious problem that can affect more people than you think. Proof Psychological anorexia (Anorexia nervosa,, or "anorexia,") most commonly affects young women and young women, but can also occur in older men and women. A recent study found that 25% of people with anorexia are men. The disease manifests itself through a strict restriction on food intake, low weight, a fear of gaining weight to the point of stress and a distorted view of the body. This is often a response to complex personal and social problems. Anorexia is a serious disorder that can cause serious bodily harm, one of the highest mortality diseases associated with mental health problems. If you think a friend or loved one has anorexia, read on to learn how to help them.

Steps

Method 1 of 5: Observe the Person's Habits

Observe the eating habits of someone you suspect of anorexia. People who do not have anorexia have an antagonistic relationship with food. The driving force behind anorexia is stressful fear of gaining weight, and they tightly limit their food intake - fasting, for example, to avoid weight gain. But fasting is only one sign of anorexia. Other potential warning signs include:- Refuse to eat certain foods or whole foods (eg, “no starch”, “no sugar”).

- There are eating patterns such as chewing too long, cutting the heels of food from the dishes, cutting food into very small pieces.

- Measure food obsessively, such as constantly counting calories, weighing food or reviewing nutritional information on labels.

- Refuse to go out to eat because it is difficult to calculate calories.

Notice if the person seems to be obsessed with food. Despite eating very little, people with anorexia often become obsessed with food. They can passionately read many food magazines, collect recipes or watch cooking programs.They may talk about food frequently, although the stories are often negative (eg, “I can't believe people eat pizza when it's so unhealthy”).- Food phobia is a common effect of lack of food. A landmark study done during the Second World War found that people who were starved often dreamed about food. They will spend strangely enough time thinking about food and often talking to other people or themselves about eating.

Reflect on whether the person is often making excuses not to eat. When it comes to a party, for example, they will say they've already eaten. Other common reasons being hospitalized to avoid food include:- I'm not hungry.

- I am on a diet / need to lose weight.

- There is nothing I like here.

- I'm sick.

- I am "sensitive to food".

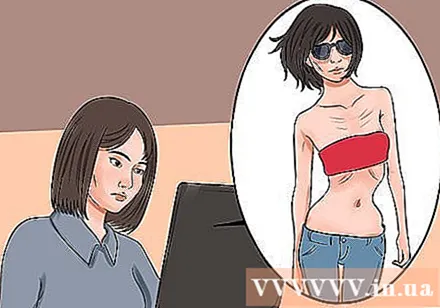

Observe if your loved one seems underweight but still talks about dieting. If the person is very thin but still says they need to lose weight, they may have a distorted view of their body. A characteristic of anorexia is the "distortion of the body", when they continue to believe that they are overweight or obese even though they are overweight. Anorexic people often deny the idea that they are underweight.

- People with anorexia can also wear loose-fitting clothes to hide their true form. They can wear layers of clothing, or wear trousers and coats even in hot weather. Part of this is to hide body size, partly because people with anorexia often cannot regulate their body temperature effectively, and therefore often feel cold.

See the person's exercise habits. People with anorexia can compensate for their food intake with exercise. Their exercises are often too heavy and very rigid.

- For example, the person usually exercises for many hours a week, even when not for a particular sport or event. They can also exercise even when tired, sick or injured because they feel the need to "burn" their caloric intake.

- Exercise is a very common compensatory behavior among men with anorexia. They often believe that they are overweight, or may not be satisfied with their physique. He may be obsessed with his bodybuilding or "demeanor". Distorted views of the body are also common among men, who are often incapable of recognizing their true form and claim that their muscles are "loose" even when they are fit. or underweight.

- People with anorexia but cannot exercise or do not do as much as they would like to experience impatience, restlessness or restlessness.

Look at the person's appearance. Anorexia causes a range of symptoms. You cannot tell if a person has anorexia by looking at their appearance. The combination of these symptoms with the disturbing behaviors is the most obvious indication that the person has an eating disorder. Not everyone with anorexia will have all of these symptoms, but they often experience many of the following:

- Lose a lot of weight, suddenly

- If they are female, they often have unusual facial or body hair

- Increased sensitivity to low temperatures

- Hair loss or thinning

- Dry, pale, or yellow skin

- Fatigue, dizziness, or fainting

- Brittle hair and nails

- Pale fingers

Method 2 of 5: Thinking about the person's emotional state

Observe the person's mood. Sudden mood swings can be very common in people with anorexia because of a hormone imbalance caused by starvation of the body. Anxiety and depression often co-exist with an eating disorder.

- People with anorexia may also feel restless, lethargic, and difficult to concentrate.

Note the person's self-esteem. People with anorexia are usually perfectionists. They can be extremely effortful people and often perform well at school or at work. However, they often have a very low self-esteem. People with anorexia often complain that they are not “good enough” or that they cannot “do anything right”.

- People with anorexia are also often very low on confidence. They may say that they are about to reach "ideal weight", but they can never do it because of a distorted view of the body. They always feel the need to lose more weight.

Notice if the person mentions guilt or shame. People with anorexia often feel very embarrassed after eating. They may see eating as a sign of weakness or loss of self-control. If your loved one often expresses feelings of guilt over eating or feels guilty or ashamed of his body size, that could be a warning sign of anorexia.

Think if they're cowering. People with anorexia often avoid friends and normal activities. They also started increasing their online time.

- Anorexic people can go to the website "pro-Ana", a group that promotes and advocates anorexia as a "lifestyle choice". It is important to remember that anorexia is a life-threatening but treatable condition, and is not a healthy choice for healthy people.

- People with anorexia can post "thin-inspired" messages on social media. These types of messages may include images of extremely underweight people mocking people of normal weight or overweight.

Notice if this person stays in the bathroom long after eating. There are two types of psychological anorexia: form binge eating and pouring out (Binge-Eating / Purging Type) and form eat less (Restricting Type). Dieting is the form of anorexia most people are familiar with, but binge and spit-eating patterns are also common. The spit may be in the form of vomiting after eating, or the person may take a laxative, enema, or diuretic.

- Anorexia / sputum is different from eating - vomiting (bulimia nervosa), another form of eating disorder. People who suffer from eating and vomiting do not usually have a calorie restriction. People with binge eating / spilling are always severely limited in calorie intake.

- People with anorexia - vomiting usually eat a lot before the lump. A person with binge eating / spilling may consider a very small amount of food "insatiable" and need to be spilled, whether it be a biscuit or a small package of potato chips.

See if the person looks mysterious. People with anorexia may feel ashamed of their disorder. Or they may think that you don't “understand” their eating behavior and often try not to show. The person often conceals his / her behaviors from judging or meddling. For example, they often:

- Eat it secretly

- Hide or throw away food

- Take weight loss pills or supplements

- Hide laxatives

- Lie about your practice

Method 3 of 5: Ask for Help

Learn about an eating disorder. You can easily judge a person with an eating disorder, but it's hard to understand why that person is doing such unhealthy things. Finding out what is causing the eating disorder and what the person is suffering will help you reach your loved one with understanding and concern.

- One good source to check out is Talking to Eating Disorders: Simple Ways to Support Someone with Anorexia, Bulimia, Binge Eating, or Body Image Issues, (Discussing eating disorders: Simple Ways to Help People anorexia, anorexia - vomiting, binge eating or body image problems) by Jeanne Albronda Heaton and Claudia J. Strauss.

- The National Dietary Disorders Association is a non-profit organization that provides a wide range of resources to friends and family of people with eating disorders. The Link for Perception of Eating Disorder is a non-profit organization that educates and provides resources to raise awareness about an eating disorder and its effects.The National Institute of Mental Health has a wealth of outstanding information and resources to support people with eating disorders and their loved ones.

Understand the real risks of anorexia. Anorexia causes the body to starve and can lead to serious medical problems. In women aged 15-24 years, psychological anorexia causes 12 times more mortality than any other cause. Up to 20% of cases of anorexia will lead to premature death. It can also cause a variety of health problems, including:

- There is no period in women

- Drowsiness and exhaustion

- Inability to regulate body temperature

- Abnormally slow or irregular heartbeat (due to weakening of the heart muscle)

- Anemia

- Infertility

- Loss of memory or disorientation

- Impaired function of organs

- Brain damage

Find a good time to talk privately with the person. An eating disorder is often a response to complex personal and social problems. It may also have genetic factors. Talking about your eating disorder can be a very embarrassing or uncomfortable topic. Make sure you reach your loved one in a safe and private place.

- Avoid approaching the person if either person is feeling angry, tired, stressed, or otherwise emotionally upset. This will make it harder for you to show your interest to the person.

Use a sentence with the theme "I" to convey your feelings. When you hear these statements, the other person may feel less like you are attacking them. Encapsulate the conversation in a way that is safe and within the other person's control. For example, you could say something like, “Recently, I see something that worries me. I care about you. Can we talk? "

- Your loved one can be on guard. They may not acknowledge they have a problem. They may blame you for interfering with their lives or judging them too harshly. You can affirm your love, that you care about them and will never judge them, but don't become defensive.

- For example, avoid saying things like "I'm just trying to help you" or "I have to listen to me." Sentences like that will make the other person feel attacked and they won't want to hear you anymore.

- Instead, focus on positive statements: "I love you and I want you to know that I am here with you" or "I am ready to talk whenever you feel ready." Give the person space to make their own decisions.

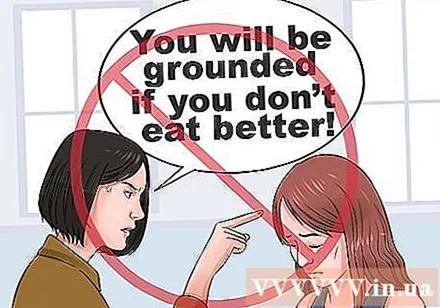

Avoid reprimanding language. Using sentences with the subject "I" will help you do this. However, it is important not to use language of reprimand or judgment. Exaggerated words, causing guilt, threats or accusations will not help the other person understand your sincere concerns.

- For example, you should avoid statements that are the subject of the other person, such as "You're making me worrying" or "You have to stop this."

- Words that embarrass the other person and feel guilty are also ineffective. For example, avoid saying things like "I think I am doing with my family" or "If I really care about you, I should take care of myself." People with anorexia may also have felt very shameful about their behavior, and such words only aggravate the disorder.

- Don't intimidate the person. For example, you should avoid statements like "You won't be able to go out of the house if you don't eat properly" or "I'll tell everyone your problem if you don't agree to let me help you." This can cause them to panic and make their illness worse.

Encourage the person to share their feelings. It's also important to give the other person time to share their feelings. One-way conversations and just talking about yourself won't work.

- Don't push your loved one when he talks. Processing emotions and thoughts takes time.

- In short, don't judge and criticize the feelings of the person you love.

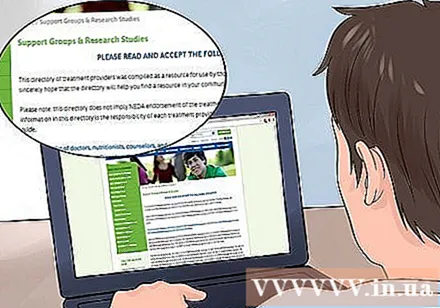

Ask the person to take the test online. The National Dietary Disorders Association (NEDA) has a free and anonymous online tool. When you ask your loved one to take this test, you can put “light pressure” on your loved one to become aware of the problem.

- NEDA has two tests: one for students, and one for adults.

Emphasize that professional support is needed. Try to show your interest in effective methods. Emphasize that anorexia is a serious condition, but has a high chance of cure with professional supervision. Remove the stereotype about seeing a therapist or counselor by letting your loved one know that seeking help is not a sign of failure or weakness, nor is it a sign that they are "mentally".

- People with anorexia have a hard time controlling their lives, so you can help your loved one accept it if you stress that seeking treatment is a courageous act and also a control. control life.

- You can think of this as a way of dealing with your health problem, which might also help you. For example, if your loved one has diabetes or cancer, you will encourage them to seek medical help. This case is no different; You just ask your loved one to seek professional help for treatment.

- NEDA has a "Seek treatment" section on their website. This section can help you find a counselor or therapist who specializes in anorexia.

- Especially if the person is young or a teenager, family therapy can be effective. Some studies have suggested that family therapy for adolescents is effective than individual therapy, as it can help to deal with ineffective family communication, while at the same time offering ways to help people support the patient.

- Some severe cases may require inpatient treatment. This is usually due to the patient being overweight and facing high risks such as functional impairment. People who are psychologically unstable or have suicidal thoughts may also need to be in hospital.

Find help for yourself. It is difficult to watch your loved one cope with an eating disorder. This is even more difficult when the person is not aware that they have a problem, which is very common in people with eating disorders. Seeking help from a therapist or support group can help you stay strong.

- NEDA has a list of support groups on their website. They also have Parents, Family & Friends Networks.

- The National Association for Anorexia and Related Disorders (ANAD) has a list of support groups.

- Your doctor may also refer you to local support groups or other resources.

- Seeking counseling is extremely essential for parents of children with anorexia. It is important not to control or indulge your child's eating behavior, but it can be difficult to accept this when looking at your baby in danger. Therapies and support groups can help you learn how to support and help your child without getting worse.

Method 4 of 5: Helping your loved one recover

Recognize the person's feelings, struggles, and accomplishments. About 60% of people with anorexia can recover with treatment. However, it can take several years for them to fully recover. Some people may feel uncomfortable with their body all the time or feel compelled to fast or binge eat, even though they try to avoid destructive behaviors. Help your loved one through this process.

- Praise their little achievements. For people with anorexia, eating even a little with your eyes signifies their great effort.

- Do not judge when the illness recurs. Make sure your loved one is well cared for, but don't criticize when he or she struggles or stumbles. Recognize the recurrence of illness and focus on how to get back on track.

Flexible and adaptable. In some cases, especially when young adults are involved, treatment may be combined with changes in habits from friends and family. Be ready to make the necessary changes for the sake of your loved one.

- For example, your doctor may suggest changing some ways of communicating and handling conflicts.

- It can be difficult to realize that what you say or do may affect a loved one's disorder. Remember you don't cause disorder, but you can help your loved one recover by changing some of your behaviors. Recovery is the ultimate goal.

Focus on something positive or happy. One can easily fall into the kind of "support" that suffocates the insider. Don't forget that people struggling with anorexia think about food, weight, and body image all day long. Don't let this confusion be the focus or the only thing in your conversations.

- For example, you can go to the movies, shop, play games or play sports with them. Treat the person with kindness and consideration, but let them enjoy life as normal as possible.

- Remember that people with an eating disorder themselves are not disturbed. They are human beings with their own needs, thoughts, and feelings.

Remind the person that they are not alone. Fighting an eating disorder can bring a great deal of isolation. While you don't want to suffocate your loved one, it's helpful to remind them that you're there to talk to and support them.

- Find support groups or other support activities your loved one can join. Don't be forced, but give them suggestions for choosing.

Help your loved one deal with stimulants. Your loved one may feel that some person, situation or event "provokes" their confusion. Seeing ice cream in front of your eyes, for example, can provoke a terrible temptation. Eating out can cause food anxiety. You should be as supportive as you can be. Sometimes it takes a while to detect stimuli that patients are also not expecting.

- Past feelings and experiences can trigger unhealthy behavior.

- New or stressful experiences and situations can also act as stimuli. Many people with anorexia have a strong desire to feel in control, and situations that make them feel insecure can provoke them to exhibit unhealthy eating behaviors.

Method 5 of 5: Avoid Making the Problem worse

Do not try to control the person's eating behavior. Do not try to force them to eat. Don't tempt a loved one to eat more or use intimidation to force them. Sometimes, anorexia is a response to a lack of control over your life. Trying to gain control or take away their control can make matters worse.

- Don't try to "fix" your loved one's problems. Recovery is as complicated as an eating disorder. Trying to "fix" a loved one in his own way can cause harm. Instead, encourage them to see a mental health professional.

Avoid commenting on the person's behavior and appearance. Anorexia is often embarrassing and embarrassing to sufferers. Even if you mean well, commenting on their appearance, eating habits, weight, etc. can cause shame and anger.

- Compliments are also in vain. People with anorexia are dealing with a distorted view of the body, so they may not believe you either. Even positive comments can be judged or dominated by them.

Avoid the stigma of being fat or thin. Healthy weights can vary from person to person. If your loved one says they are "fat," it's important to you are not react by saying things like, "I'm not fat". This only reinforces the unhealthy notion that "fat" is a bad thing that people fear and avoid.

- Similarly, don't point at thin people and comment on their looks, like "Nobody wants to hug a skinny person." If you want your loved one to develop a healthy image of the body, don't focus on your fears or downplay a particular type of body shape.

- Instead, ask your loved one from where they got that feeling. Ask them what they gain when they lose weight, or what they fear if they feel overweight.

Avoid simplifying the problem. Anorexia and other eating disorders are complex and often go hand in hand with other medical conditions such as anxiety and depression. Peer peer pressure and media can play as important a role as family and social background. When you say things like "You eat more, everything will be fine", you ignore the complexity of the problem your loved one is struggling with.- Instead, show your support by saying, "I know it's a hard time for you now" or "Changing eating habits can be difficult, and I believe. in children ”.

Avoid perfectionism. Striving to be "perfect" is a common stimulant that causes anorexia. However, perfectionism is an unhealthy way of thinking; it prevents resilience and flexibility, which is an important part of success in life. It ties you and others to an unworkable, unrealistic, and ever-changing standard. Don't expect perfection from loved ones or yourself. It can take a long time to cure an eating disorder, and both you and the other person will have times to regret doing things.- Know when you've done something wrong, but don't pay attention to it or torment yourself. Instead, focus on what you can do to avoid similar mistakes.

Don't promise to "keep it a secret". It may be easy to agree to keep a loved one's disorder a secret to gain their trust. However, you don't want to encourage the person's behavior. Anorexia can cause death in up to 20% of people with the disease. It is important to encourage your loved one to accept help.- Understand that your loved one may be angry at first or even dismiss your suggestion that they need help. This is normal. Stay by their side and let them know that you are ready to support and care for them.

Advice

- Maintaining a healthy diet and exercise routine is different from an eating disorder. People interested in diet and regular exercise can have perfect health. If you notice that a person is obsessed with food and / or exercise, especially if they appear anxious or lie about them, you probably have reason to worry.

- Never assume that someone has anorexia just because they are thin. Also never assume that someone does not have anorexia just because they are not too skinny. You cannot tell if a person has anorexia just by their physical appearance.

- Don't make fun of the person you think has anorexia. People with anorexia are often lonely, sad and distressed. They may be anxious, depressed, or even suicidal. They should not be criticized; This only made the situation worse.

- Do not force the person to eat outside of the therapy program. People with anorexia can be very sick, and even if they are okay without eating, adding more calories can make people with anorexia go hungry and exercise, and exacerbate the health problem.

- Bear in mind that if a person suffers from anorexia, it is not anyone's fault. Do not be afraid to admit the problem, and do not be prejudiced about people with anorexia.

- If you think that you or someone you know might have anorexia, talk to someone you trust. Tell the teacher, counselor, spiritual figure, or parent. Seek expert advice. Help is always available, but you can't get help if you don't have the courage to say it.

== Source and Quote ==

- ↑ Wooldridge, T., & Lytle, P. “. (2012). An Overview of Anorexia Nervosa in Males. Eating Disorders, 20 (5), 368-378. Doi: 10.1080 / 10640266.2012.715515

- ↑ http://www.dsm5.org/documents/eating%20disorders%20fact%20sheet.pdf

- ↑ https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/anorexia-nervosa

- ↑ https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/anorexia-nervosa

- ↑ http://www.allianceforeatingdisorders.com/portal/signs-of-anorexia#.VT-AWiFViko

- ↑ http://www.medicinenet.com/anorexia_nervosa/page5.htm#what_are_anorexia_symptoms_and_signs_psychological_and_behavioral

- ↑ http://www.apa.org/monitor/2013/10/hunger.aspx

- ↑ http://www.allianceforeatingdisorders.com/portal/signs-of-anorexia#.VT-AWiFViko

- ↑ https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/anorexia-nervosa

- ↑ http://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/anorexia-nervosa-males

- ↑ Strother, E., Lemberg, R., Stanford, S. C., & Turberville, D. (2012). Eating Disorders in Men: Underdiagnosed, Undertreated, and Misunderstood. Eating Disorders, 20 (5), 346-355. Doi: 10.1080 / 10640266.2012.715512

- ↑ http://www.nimh.nih.gov/news/science-news/2014/9-eating-disorders-myths-busted.shtml

- ↑ http://www.anad.org/get-information/get-informationanorexia-nervosa/

- ↑ https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/anorexia-nervosa

- ↑ http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/anorexia/basics/symptoms/con-20033002

- ↑ http://www.anad.org/get-information/eating-disorder-signs-and-symptoms/

- ↑ http://eatingdisorder.org/eating-disorder-information/anorexia-nervosa/

- ↑

- ↑ http://www.medicinenet.com/anorexia_nervosa/page5.htm#what_are_anorexia_symptoms_and_signs_psychological_and_behavioral

- ↑ https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/anorexia-nervosa

- ↑ http://www.allianceforeatingdisorders.com/portal/signs-of-anorexia#.VT-AWiFViko

- ↑ https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/anorexia-nervosa

- ↑ http://eatingdisorder.org/eating-disorder-information/anorexia-nervosa/

- ↑ https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/anorexia-nervosa

- ↑ http://www.anad.org/get-information/bulimia-nervosa/

- ↑ http://www.anad.org/get-information/get-informationanorexia-nervosa/

- ↑ Becker, A. E., Eddy, K. T., & Perloe, A. (2009). Clarifying criteria for cognitive signs and symptoms for eating medical in DSM-V. International Journal Of Eating Disorders, 42 (7), 611-619. DOI: 10.1002 / eat.20723

- ↑ http://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/parent-family-friends-network

- ↑ http://www.allianceforeatingdisorders.com/portal/who-we-are

- ↑ http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/eating-disorders/index.shtml

- ↑ https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/get-facts-eating-disorders

- ↑ https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/get-facts-eating-disorders

- ↑ http://www.allianceforeatingdisorders.com/portal/did-you-know#.VT-e9CFViko

- ↑ http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/eating-disorders/index.shtml#part_145415

- ↑ http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/eating-disorders/index.shtml

- ↑ http://www.nedc.com.au/what-to-say-and-do

- ↑ http://www.nedc.com.au/what-to-say-and-do

- ↑ http://www.nedc.com.au/what-to-say-and-do

- ↑ http://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/online-eating-disorder-screening

- ↑ https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/anorexia-nervosa

- ↑ http://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/find-treatment/treatment-and-support-groups

- ↑ http://med.stanford.edu/news/all-news/2010/10/family-therapy-for-anorexia-more-effective-than-individual-therapy-researchers-find.html

- ↑ https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/treatment-settings-and-levels-care

- ↑ http://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/find-treatment/support-groups-research-studies

- ↑ http://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/parent-family-friends-network

- ↑ http://www.anad.org/eating-disorders-get-help/eating-disorders-support-groups/

- ↑ http://www.anred.com/stats.html

- ↑ http://www.allianceforeatingdisorders.com/portal/how-to-help-a-loved-one#.VT-XBCFViko

- ↑ http://www.anred.com/causes.html

- ↑ http://www.allianceforeatingdisorders.com/portal/how-to-help-a-loved-one#.VT-XZCFVikp

- ↑ http://www.helpguide.org/articles/eating-disorders/helping-someone-with-an-eating-disorder.htm

- ↑ http://www.helpguide.org/articles/eating-disorders/helping-someone-with-an-eating-disorder.htm

- ↑ http://nymag.com/scienceofus/2014/09/alarming-new-research-on-perfectionism.html

- ↑ http://www.healthychildren.org/English/ages-stages/young-adult/Pages/The-Problem-with-Perfectionism.aspx

- ↑ http://www.anad.org/get-information/about-eating-disorders/eating-disorders-statistics/