Author:

Gregory Harris

Date Of Creation:

11 August 2021

Update Date:

22 June 2024

Content

The purpose of this article is to summarize the steps in the application of general anesthesia.

Steps

1 Determine the clinical findings. Review history, physical examination, and laboratory results to identify underlying clinical considerations for the patient (eg, limited mouth opening, hypertension, angina pectoris, bronchial asthma, anemia, etc.). Determine the patient's physical condition according to the ASA (American Society of Anesthesiology) criteria. Sometimes just one or two suggestions will suffice: Mr. Desai is a mostly healthy ASA II 81 kg 46-year-old man with chronic anemia (hematocrit = 0.29) and controlled hypertension (atenolol 25 mg twice daily) who is scheduled for partial colectomy under general anesthesia. He has no allergies and his functional profile is negative.

1 Determine the clinical findings. Review history, physical examination, and laboratory results to identify underlying clinical considerations for the patient (eg, limited mouth opening, hypertension, angina pectoris, bronchial asthma, anemia, etc.). Determine the patient's physical condition according to the ASA (American Society of Anesthesiology) criteria. Sometimes just one or two suggestions will suffice: Mr. Desai is a mostly healthy ASA II 81 kg 46-year-old man with chronic anemia (hematocrit = 0.29) and controlled hypertension (atenolol 25 mg twice daily) who is scheduled for partial colectomy under general anesthesia. He has no allergies and his functional profile is negative.  2 Consulting. Make sure that all necessary consultations have been carried out (for example, patients with diabetes mellitus may need an endocrinologist consultation; patients with myasthenia gravis will need neurological consultation). Here are some other occasional situations where formal or informal counseling may be appropriate: recent myocardial infarction, decreased left ventricular function (decreased ejection fraction), pulmonary hypertension, metabolic disorders such as severe hyperkalemia, uncontrolled severe hypertension, mitral or aortic stenosis, pheochromocytoma, coagulopathy, suspected airway problems

2 Consulting. Make sure that all necessary consultations have been carried out (for example, patients with diabetes mellitus may need an endocrinologist consultation; patients with myasthenia gravis will need neurological consultation). Here are some other occasional situations where formal or informal counseling may be appropriate: recent myocardial infarction, decreased left ventricular function (decreased ejection fraction), pulmonary hypertension, metabolic disorders such as severe hyperkalemia, uncontrolled severe hypertension, mitral or aortic stenosis, pheochromocytoma, coagulopathy, suspected airway problems  3 Airway assessment. Assess the patient's airway with the Mallampati System and examine the patient's oropharynx. Consider also other criteria (degree of mouth opening, head tilt and extension, jaw size, "mandibular space"). Take a close look at any loose, false, or filled teeth. Warn patients with poor teeth that intubation carries the risk of chipping or loose teeth.Determine if special airway management techniques are needed (eg, use of a video laryngoscope, glidescope, Bullard laryngoscope, or gentle intubation using a fiberoptic bronchoscope).

3 Airway assessment. Assess the patient's airway with the Mallampati System and examine the patient's oropharynx. Consider also other criteria (degree of mouth opening, head tilt and extension, jaw size, "mandibular space"). Take a close look at any loose, false, or filled teeth. Warn patients with poor teeth that intubation carries the risk of chipping or loose teeth.Determine if special airway management techniques are needed (eg, use of a video laryngoscope, glidescope, Bullard laryngoscope, or gentle intubation using a fiberoptic bronchoscope).  4 Agreement. Make sure that the consent for the transaction has been obtained and that it is correctly signed and dated. Patients who are unable to give routine consent require special consideration: patients in coma, children, patients in psychiatric hospitals, etc. Some centers require separate consents for anesthesia and blood transfusion. Central to proper agreement is that the patient is aware of all the options and their respective benefits and risks. It is not enough for the patient to simply agree and sign all the proposed documents.

4 Agreement. Make sure that the consent for the transaction has been obtained and that it is correctly signed and dated. Patients who are unable to give routine consent require special consideration: patients in coma, children, patients in psychiatric hospitals, etc. Some centers require separate consents for anesthesia and blood transfusion. Central to proper agreement is that the patient is aware of all the options and their respective benefits and risks. It is not enough for the patient to simply agree and sign all the proposed documents.  5 Blood product planning. Ensure that all necessary blood products are available (erythrocytes, platelets, canned plasma, fresh frozen plasma, cryoprecipitate, depending on the clinical situation). Most small surgical cases have blood tests for "typing and examining" blood typing and ABO / Rh antibody screening, which can make blood typing difficult. Group and type: In large surgical cases, there are often more blood units (usually red blood cells specially tested for the patient and more or less available immediately (eg 4 packs of red blood cells for cardiac patients in the operating room refrigerator).

5 Blood product planning. Ensure that all necessary blood products are available (erythrocytes, platelets, canned plasma, fresh frozen plasma, cryoprecipitate, depending on the clinical situation). Most small surgical cases have blood tests for "typing and examining" blood typing and ABO / Rh antibody screening, which can make blood typing difficult. Group and type: In large surgical cases, there are often more blood units (usually red blood cells specially tested for the patient and more or less available immediately (eg 4 packs of red blood cells for cardiac patients in the operating room refrigerator).  6 Prevention of aspiration. Make sure that the patient has not had anything in the mouth ("Zero Oral") for a specified amount of time, ie. ensure that the patient has an empty stomach (Patients with a non-empty stomach may need a rapid induction sequence, careful intubation, or the use of local or regional anesthesia to reduce the chance of regurgitation and aspiration). Pharmacological agents to reduce stomach volume and / or acidity may be appropriate before surgery, for example, particle-free oral antacid (sodium citrate 0.3 molar 30 ml orally prior to induction of anesthesia) or agents such as cimetidine, ranitidine, or famotidine (Pepcid) ...

6 Prevention of aspiration. Make sure that the patient has not had anything in the mouth ("Zero Oral") for a specified amount of time, ie. ensure that the patient has an empty stomach (Patients with a non-empty stomach may need a rapid induction sequence, careful intubation, or the use of local or regional anesthesia to reduce the chance of regurgitation and aspiration). Pharmacological agents to reduce stomach volume and / or acidity may be appropriate before surgery, for example, particle-free oral antacid (sodium citrate 0.3 molar 30 ml orally prior to induction of anesthesia) or agents such as cimetidine, ranitidine, or famotidine (Pepcid) ...  7 Determine the mode of monitoring needs. All patients undergoing surgery receive the following routine monitoring: Non-invasive blood pressure monitoring (manual or automatic), airway pressure monitoring / alarm deactivation, ECG, neurostimulator, pulse oximeter, urometer (if a Foley catheter is placed), airway monitoring, gas analyzer (including oxygen analyzer and capnograms), body temperature. In addition, spirometry (tidal volume / minute volume) and agent analyzers (% isoflurane,% nitrous oxide, etc.) are highly desirable. Body temperature can be measured in the armpit, nasopharynx, esophagus, or rectum.

7 Determine the mode of monitoring needs. All patients undergoing surgery receive the following routine monitoring: Non-invasive blood pressure monitoring (manual or automatic), airway pressure monitoring / alarm deactivation, ECG, neurostimulator, pulse oximeter, urometer (if a Foley catheter is placed), airway monitoring, gas analyzer (including oxygen analyzer and capnograms), body temperature. In addition, spirometry (tidal volume / minute volume) and agent analyzers (% isoflurane,% nitrous oxide, etc.) are highly desirable. Body temperature can be measured in the armpit, nasopharynx, esophagus, or rectum.  8 Determine the specific monitoring needs of CVP (Central Venous Pressure) PA (Pulmonary Artery). Determine if special monitors are needed (arterial line, CVP lines, PA line, etc.). Arterial lines allow monitoring of blood pressure at each heartbeat, control of arterial blood gas and easy access to blood for tests. The CVP line is useful for assessing right-sided cardiac filling pressure. PA lines are useful for measuring cardiac output or when right-sided heart filling pressure does not reflect what is happening on the left side. PA catheters measurements: (1) CVP waveform (2) PA waveform (3) PCWP ("wedge pressure") (4) Cardiac output (5) Right-sided resistance (PVR - pulmonary vascular resistance) (6) Left-sided resistance (SVR) - vascular resistance system) (7) PA temperature.Induced potential studies are sometimes useful for monitoring the brain and spinal cord during neurosurgical and orthopedic procedures.

8 Determine the specific monitoring needs of CVP (Central Venous Pressure) PA (Pulmonary Artery). Determine if special monitors are needed (arterial line, CVP lines, PA line, etc.). Arterial lines allow monitoring of blood pressure at each heartbeat, control of arterial blood gas and easy access to blood for tests. The CVP line is useful for assessing right-sided cardiac filling pressure. PA lines are useful for measuring cardiac output or when right-sided heart filling pressure does not reflect what is happening on the left side. PA catheters measurements: (1) CVP waveform (2) PA waveform (3) PCWP ("wedge pressure") (4) Cardiac output (5) Right-sided resistance (PVR - pulmonary vascular resistance) (6) Left-sided resistance (SVR) - vascular resistance system) (7) PA temperature.Induced potential studies are sometimes useful for monitoring the brain and spinal cord during neurosurgical and orthopedic procedures.  9 Premedication. Order preoperative sedations, desiccants, antacids, H2 blockers, or other medication as needed. For example: Premedication of orders - Preoperative sedation - diazepam 10 mg orally with a sip of water 90 min orally; midazolam 1 mg intravenously in the waiting area at the request of the patient; morphine 10 mg / Trilaphon (perphenazine) 2.5 mg IM one oral (heavier). Desiccant (eg, before careful intubation) glycopyrrolate 0.4 mg IM alone orally. Decrease in gastric acidity (for example, in patients with aspiration risk) - ranitidine 150 mg orally in the evening before surgery and again at night; Heart prophylaxis (eg, mitral stenosis) - AHA (American Heart Association) antibiotics

9 Premedication. Order preoperative sedations, desiccants, antacids, H2 blockers, or other medication as needed. For example: Premedication of orders - Preoperative sedation - diazepam 10 mg orally with a sip of water 90 min orally; midazolam 1 mg intravenously in the waiting area at the request of the patient; morphine 10 mg / Trilaphon (perphenazine) 2.5 mg IM one oral (heavier). Desiccant (eg, before careful intubation) glycopyrrolate 0.4 mg IM alone orally. Decrease in gastric acidity (for example, in patients with aspiration risk) - ranitidine 150 mg orally in the evening before surgery and again at night; Heart prophylaxis (eg, mitral stenosis) - AHA (American Heart Association) antibiotics  10 Intravenous access. Begin an intravenous (IV) injection from an appropriately sized catheter into the arm or forearm (first using local anesthesia for a large IV catheter.) In most cases, a 20, 18, or 16 gauge intravenous catheter is connected to a bag of saline (0.9%) or lactated Ringer's solution is commonly used. The large size 14 is often used in cardiac cases and other large cases, or when there is concern that the patient is hypovolemic. In some cases (eg trauma), more than one intravenous catheter will be required or a warmer fluid will be required to avoid hypothermia. In other cases, an intravenous catheter is inserted through the center line, as in a line located in the internal jugular vein, external jugular vein, or subclavian vein.

10 Intravenous access. Begin an intravenous (IV) injection from an appropriately sized catheter into the arm or forearm (first using local anesthesia for a large IV catheter.) In most cases, a 20, 18, or 16 gauge intravenous catheter is connected to a bag of saline (0.9%) or lactated Ringer's solution is commonly used. The large size 14 is often used in cardiac cases and other large cases, or when there is concern that the patient is hypovolemic. In some cases (eg trauma), more than one intravenous catheter will be required or a warmer fluid will be required to avoid hypothermia. In other cases, an intravenous catheter is inserted through the center line, as in a line located in the internal jugular vein, external jugular vein, or subclavian vein.  11 Equipment preparation. ANSWER CHECK (BASIC POINTS ONLY - SEE ENTIRE LIST): Oxygen concentrator, oxygen flow meter, nitrogen concentrator, nitrogen flow meter, check oxygen cylinder, check for leaks, check evaporator, check fan. CHECKING THE RESPIRATORY EQUIPMENT: suction, oxygen, laryngoscope, endotracheal tube, endotracheal probe "ends".

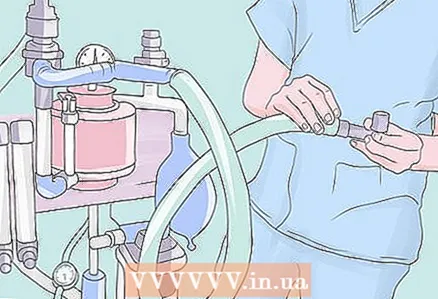

11 Equipment preparation. ANSWER CHECK (BASIC POINTS ONLY - SEE ENTIRE LIST): Oxygen concentrator, oxygen flow meter, nitrogen concentrator, nitrogen flow meter, check oxygen cylinder, check for leaks, check evaporator, check fan. CHECKING THE RESPIRATORY EQUIPMENT: suction, oxygen, laryngoscope, endotracheal tube, endotracheal probe "ends".  12 Preparation of medicines. Prepare medicines in labeled syringes. Examples: thiopental, propofol, fentanyl, midazolam, succinylcholine, rocuronium. Not all of these drugs will be needed in every case (for example, usually only one induction of the agent is required).

12 Preparation of medicines. Prepare medicines in labeled syringes. Examples: thiopental, propofol, fentanyl, midazolam, succinylcholine, rocuronium. Not all of these drugs will be needed in every case (for example, usually only one induction of the agent is required).  13 Preparing an emergency medicine: atropine, ephedrine, phenylephrine, nitroglycerin, esmolol. In low-risk cases, you do not need any of these drugs to be ready instantly. High-risk cases may also require dopamine, epinephrine, norepinephrine, and other drugs.

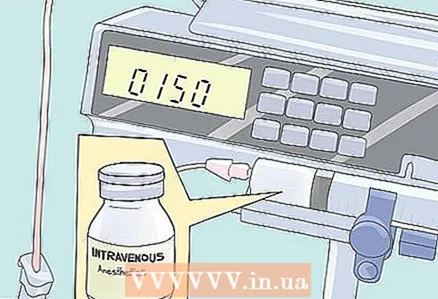

13 Preparing an emergency medicine: atropine, ephedrine, phenylephrine, nitroglycerin, esmolol. In low-risk cases, you do not need any of these drugs to be ready instantly. High-risk cases may also require dopamine, epinephrine, norepinephrine, and other drugs.  14 Attach the monitors to the patient. Before induction of general anesthesia, connect an ECG, tonometer and pulse oximeter and measure baseline vital signs. Intravenous catheters should also be tested prior to drug induction. Following induction / intubation, a capnograph, airway pressure monitors, neuromuscular blockages, and a temperature probe should be attached. Dedicated monitors (CVP, arterial line, induced potentials, thoracic Doppler) may also be needed.

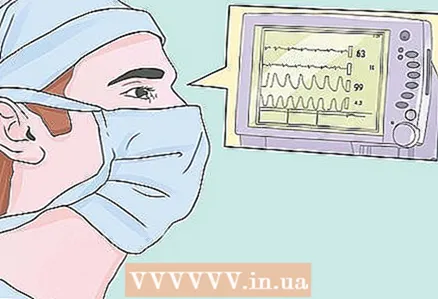

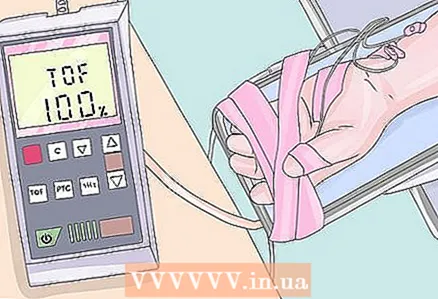

14 Attach the monitors to the patient. Before induction of general anesthesia, connect an ECG, tonometer and pulse oximeter and measure baseline vital signs. Intravenous catheters should also be tested prior to drug induction. Following induction / intubation, a capnograph, airway pressure monitors, neuromuscular blockages, and a temperature probe should be attached. Dedicated monitors (CVP, arterial line, induced potentials, thoracic Doppler) may also be needed.  15 Give pre-inlet preparations. Rocuronium 3 to 5 mg IV may be given to prevent fasciculation (followed by myalgia) from succinylcholine (a fast-acting, ultra-short-acting intravenous depolarizing muscle relaxant used primarily for intubation). Small doses of midazolam (eg, 1–2 mg IV) and / or fentanyl (eg, 50–100 mcg IV) may be given to "smooth" the induction. Larger doses may be appropriate where fewer than usual doses of thiopental or propofoal are planned (eg, in cardiac patients).Pre-start hemodynamic "adjustment" with nitroglycerin or esmolol may be necessary for patients with hypertension or patients with coronary heart disease.

15 Give pre-inlet preparations. Rocuronium 3 to 5 mg IV may be given to prevent fasciculation (followed by myalgia) from succinylcholine (a fast-acting, ultra-short-acting intravenous depolarizing muscle relaxant used primarily for intubation). Small doses of midazolam (eg, 1–2 mg IV) and / or fentanyl (eg, 50–100 mcg IV) may be given to "smooth" the induction. Larger doses may be appropriate where fewer than usual doses of thiopental or propofoal are planned (eg, in cardiac patients).Pre-start hemodynamic "adjustment" with nitroglycerin or esmolol may be necessary for patients with hypertension or patients with coronary heart disease.  16 Introduction of general anesthesia. Tell the patient that he / she will fall asleep. Measure your baseline vital signs. The use of thiopental (eg 3-5 mg / kg), propofol (eg 2-3 mg / kg), or other intravenous drugs will render the patient unconscious. (Consider using etomidate or ketamine for hypovolemic patients. Consider using fentanyl or sufentanil as the primary induction agent for cardiac cases. Using inhalation induction with a potent agent such as sevoflurane will also work, but much less popular in adults.)

16 Introduction of general anesthesia. Tell the patient that he / she will fall asleep. Measure your baseline vital signs. The use of thiopental (eg 3-5 mg / kg), propofol (eg 2-3 mg / kg), or other intravenous drugs will render the patient unconscious. (Consider using etomidate or ketamine for hypovolemic patients. Consider using fentanyl or sufentanil as the primary induction agent for cardiac cases. Using inhalation induction with a potent agent such as sevoflurane will also work, but much less popular in adults.)  17 Provide muscle relaxation (after making sure you can ventilate the patient with a mask, if a dose of a non-depolarizing neuromuscular blocker is given and the patient cannot be ventilated with a mask, emergency efforts such as a tracheostomy may become necessary to revive the patient). After the patient becomes unconscious, as evidenced by loss of eyelid reflex, use a depolarizing muscle relaxant such as succinylcholine or a non-depolarizing agent such as rocuronium or vecuronium to paralyze the patient to facilitate endotracheal intubation. Succinylcholine is popular in this situation due to its rapid onset and end of exposure (short duration of effect), but many physicians never use succinylcholine regularly because of its sometimes fatal side effects associated with hyperkalemia and because it can initiate malignancy in susceptible patients. hyperthermia. The effects of muscle relaxants can be controlled by using a nerve stimulator ("twitch monitoring"), as well as by observing unwanted movements of the patient. (This step is not necessary if a mask or laryngeal mask is used, or if the intubated patient is awake.)

17 Provide muscle relaxation (after making sure you can ventilate the patient with a mask, if a dose of a non-depolarizing neuromuscular blocker is given and the patient cannot be ventilated with a mask, emergency efforts such as a tracheostomy may become necessary to revive the patient). After the patient becomes unconscious, as evidenced by loss of eyelid reflex, use a depolarizing muscle relaxant such as succinylcholine or a non-depolarizing agent such as rocuronium or vecuronium to paralyze the patient to facilitate endotracheal intubation. Succinylcholine is popular in this situation due to its rapid onset and end of exposure (short duration of effect), but many physicians never use succinylcholine regularly because of its sometimes fatal side effects associated with hyperkalemia and because it can initiate malignancy in susceptible patients. hyperthermia. The effects of muscle relaxants can be controlled by using a nerve stimulator ("twitch monitoring"), as well as by observing unwanted movements of the patient. (This step is not necessary if a mask or laryngeal mask is used, or if the intubated patient is awake.)  18 Intubate the patient (protect the airway). Using your left gloved hand, insert a laryngoscope to visualize the epiglottis and vocal cords, and then insert an endotracheal tube (ETT) through the retracted vocal cords with your right hand. Typically, the endotracheal tube should be located from the lips about 21 cm for women and 23 cm for men. Inflate the endotracheal tube cuff with 25 cm H2O to establish the seal (about 5 ml of air is usually sufficient), then connect the endotracheal tube to the patient's breathing circuit. Check with a stethoscope the constancy of the air intake and the correctness of the capnograms that appear. (If a laryngeal airway mask is used, it is inserted without a laryngoscope.)

18 Intubate the patient (protect the airway). Using your left gloved hand, insert a laryngoscope to visualize the epiglottis and vocal cords, and then insert an endotracheal tube (ETT) through the retracted vocal cords with your right hand. Typically, the endotracheal tube should be located from the lips about 21 cm for women and 23 cm for men. Inflate the endotracheal tube cuff with 25 cm H2O to establish the seal (about 5 ml of air is usually sufficient), then connect the endotracheal tube to the patient's breathing circuit. Check with a stethoscope the constancy of the air intake and the correctness of the capnograms that appear. (If a laryngeal airway mask is used, it is inserted without a laryngoscope.)  19 Ventilate the patient. Although in many cases this can be done by the patient's spontaneous breathing "breathe on his own", in all cases with the use of muscle relaxants, artificial ventilation of the lungs is necessary at this time. REGULAR VENTILATION SETTINGS: tidal volume 8-10 ml / kg. Respiratory rate 8-12 / min. Oxygen concentration 30%. NOTE: Aim for a PCO2 carbon dioxide partial pressure of 35-40 mmHg in normal cases and 28-32 mmHg in some patients with increased intracranial pressure. Ensure that all ventilation related alarms (apnea, high airway pressure, etc.) are turned on and properly set.

19 Ventilate the patient. Although in many cases this can be done by the patient's spontaneous breathing "breathe on his own", in all cases with the use of muscle relaxants, artificial ventilation of the lungs is necessary at this time. REGULAR VENTILATION SETTINGS: tidal volume 8-10 ml / kg. Respiratory rate 8-12 / min. Oxygen concentration 30%. NOTE: Aim for a PCO2 carbon dioxide partial pressure of 35-40 mmHg in normal cases and 28-32 mmHg in some patients with increased intracranial pressure. Ensure that all ventilation related alarms (apnea, high airway pressure, etc.) are turned on and properly set.  20 Look at oxygen saturation. Indoor air contains 21% oxygen. Under anesthesia, patients are given a minimum 30 percent oxygen (Exception: Cancer patients who have taken bleomycin receive only 21 percent oxygen to reduce the likelihood of oxygen toxicity).100 percent oxygen with aggressive PEEP (positive end expiratory pressure) may be required by patients with severe respiratory distress (such as acute respiratory distress syndrome). Aim for a pulse oximeter reading (arterial oxygen saturation) above 95%. Drops in arterial oxygenation are often the result of intubation of the tube into the right bronchus - check for equal air supply in all such cases.

20 Look at oxygen saturation. Indoor air contains 21% oxygen. Under anesthesia, patients are given a minimum 30 percent oxygen (Exception: Cancer patients who have taken bleomycin receive only 21 percent oxygen to reduce the likelihood of oxygen toxicity).100 percent oxygen with aggressive PEEP (positive end expiratory pressure) may be required by patients with severe respiratory distress (such as acute respiratory distress syndrome). Aim for a pulse oximeter reading (arterial oxygen saturation) above 95%. Drops in arterial oxygenation are often the result of intubation of the tube into the right bronchus - check for equal air supply in all such cases.  21 Calculate inhalation anesthesia. Maintain anesthesia with 70% nitrous oxide (N2O), 30% oxygen and a potent inhalation agent such as isoflurane (eg 1%). Using blood pressure, heart rate, and other anesthetic depth readings, adjust the required inhaled reagent concentration (or increase the amount of intravenous agents such as fentanyl or propofol). Other volatiles used in general anesthesia include sevoflurane, desflurane, or halothane. Ether is still used in some countries.

21 Calculate inhalation anesthesia. Maintain anesthesia with 70% nitrous oxide (N2O), 30% oxygen and a potent inhalation agent such as isoflurane (eg 1%). Using blood pressure, heart rate, and other anesthetic depth readings, adjust the required inhaled reagent concentration (or increase the amount of intravenous agents such as fentanyl or propofol). Other volatiles used in general anesthesia include sevoflurane, desflurane, or halothane. Ether is still used in some countries.  22 Add intravenous anesthesia. Add fentanyl, midazolam, propofol, and other anesthetics as needed according to your clinical judgment of the depth of anesthesia. Supplements of fentanyl (50-100 mcg) will help maintain analgesia. Some doctors prefer intravenous technique to everything - total intravenous anesthesia, or general intravenous anesthesia. This may be beneficial for patients with a predisposition to malignant hyperthermia (which succinylcholine or potent inhalers such as desflurane, sevoflurane, or isoflurane cannot provide).

22 Add intravenous anesthesia. Add fentanyl, midazolam, propofol, and other anesthetics as needed according to your clinical judgment of the depth of anesthesia. Supplements of fentanyl (50-100 mcg) will help maintain analgesia. Some doctors prefer intravenous technique to everything - total intravenous anesthesia, or general intravenous anesthesia. This may be beneficial for patients with a predisposition to malignant hyperthermia (which succinylcholine or potent inhalers such as desflurane, sevoflurane, or isoflurane cannot provide).  23 Add muscle relaxants. Muscle relaxation is essential for abdominal surgery and many other clinical situations. Using a neuromuscular block monitor, add muscle relaxants as needed. (The degree of neuromuscular blockade is assessed by examining the pattern of movement of the fingers when the ulnar nerve is stimulated by an electrical series of four high-voltage discharges at intervals of 500 milliseconds from each other.) Remember that not all cases require muscle relaxation and that all patients receiving muscle relaxants should be mechanically ventilated.

23 Add muscle relaxants. Muscle relaxation is essential for abdominal surgery and many other clinical situations. Using a neuromuscular block monitor, add muscle relaxants as needed. (The degree of neuromuscular blockade is assessed by examining the pattern of movement of the fingers when the ulnar nerve is stimulated by an electrical series of four high-voltage discharges at intervals of 500 milliseconds from each other.) Remember that not all cases require muscle relaxation and that all patients receiving muscle relaxants should be mechanically ventilated.  24 Fluid control. Check for adequacy of hematocrit, coagulation, intravascular volume, and urine output by giving adequate intravenous fluid and blood products. In most cases, infuse intravenous saline or Ringer's solution to start at 250 ml / hour and then adjust to achieve the following goals: [1] In the first two hours, replace any preoperative fluid deficits (for example, “nothing by mouth” fluid retention for 8 hours x 125 ml it is necessary to keep "nothing by mouth" 1000 ml per hour to give in the first 2 hours) [2] hour (for example, 2 for carpal tunnel repair, 5 for cholecystectomy, 10 for bowel surgery) [3] Maintaining urine output over 50 ml / h or 0.5 to 1.0 ml / kg / h [4] Maintaining hematocrit at a safe range (above 0.24 for all; at or above 0.3 for selected patients at risk).

24 Fluid control. Check for adequacy of hematocrit, coagulation, intravascular volume, and urine output by giving adequate intravenous fluid and blood products. In most cases, infuse intravenous saline or Ringer's solution to start at 250 ml / hour and then adjust to achieve the following goals: [1] In the first two hours, replace any preoperative fluid deficits (for example, “nothing by mouth” fluid retention for 8 hours x 125 ml it is necessary to keep "nothing by mouth" 1000 ml per hour to give in the first 2 hours) [2] hour (for example, 2 for carpal tunnel repair, 5 for cholecystectomy, 10 for bowel surgery) [3] Maintaining urine output over 50 ml / h or 0.5 to 1.0 ml / kg / h [4] Maintaining hematocrit at a safe range (above 0.24 for all; at or above 0.3 for selected patients at risk).  25 Monitor the depth of anesthesia. Unintentional intraoperative consciousness during surgery is rare, but it is a real tragedy for the patient and can cause PTSD. This can happen when the vaporizer is accidentally emptied or another problem occurs (for example, the infusion pump has failed). Remember that when surgical patients wake up, they cannot show physical pain if they are paralyzed by muscle relaxants. Using clinical judgment, ensure that the patient is unconscious.This is more art than science, but takes into account autonomic inferences such as blood pressure and heart rate and the amount of medication administered to date. The use of a powerful inhalation agent such as fluorinated ether is especially likely to induce unconsciousness. BIS monitoring (bispectral index monitoring) often acts as an anesthetic depth monitor.

25 Monitor the depth of anesthesia. Unintentional intraoperative consciousness during surgery is rare, but it is a real tragedy for the patient and can cause PTSD. This can happen when the vaporizer is accidentally emptied or another problem occurs (for example, the infusion pump has failed). Remember that when surgical patients wake up, they cannot show physical pain if they are paralyzed by muscle relaxants. Using clinical judgment, ensure that the patient is unconscious.This is more art than science, but takes into account autonomic inferences such as blood pressure and heart rate and the amount of medication administered to date. The use of a powerful inhalation agent such as fluorinated ether is especially likely to induce unconsciousness. BIS monitoring (bispectral index monitoring) often acts as an anesthetic depth monitor.  26 Prevent hypothermia. Perioperative hypothermia can be a serious problem in some patients. For example, patients who tremble in the recovery room after surgery consume excess oxygen and can "increase the load on the heart" (cause myocardial ischemia in patients with coronary artery disease). Keep the temperature above 35 Celsius with liquid heaters, use air heaters, or simply keep the room warm. Measure axillary, rectal, or oropharyngeal temperature to determine the degree of hypothermia. Temperature control also helps detect the occurrence of malignant hyperthermia (hypermetabolic syndrome).

26 Prevent hypothermia. Perioperative hypothermia can be a serious problem in some patients. For example, patients who tremble in the recovery room after surgery consume excess oxygen and can "increase the load on the heart" (cause myocardial ischemia in patients with coronary artery disease). Keep the temperature above 35 Celsius with liquid heaters, use air heaters, or simply keep the room warm. Measure axillary, rectal, or oropharyngeal temperature to determine the degree of hypothermia. Temperature control also helps detect the occurrence of malignant hyperthermia (hypermetabolic syndrome).  27 Extraordinary circumstances. When surgery is nearing completion, stop giving anesthetics and reverse any neuromuscular blockade (eg, neostigmine 2.5 to 5 mg IV with 1.2 mg atropine or 0.4 mg IV glycopyrrolate). Neostigmine is never given alone (or your patient will have severe bradycardia or cardiac arrest). Use a neuromuscular blockage monitor (neurostimulator) so that any muscle relaxations are well restored. Allow spontaneous ventilation to resume. Check the breathing pattern visually and with a capnograph. Wait for the return of consciousness.

27 Extraordinary circumstances. When surgery is nearing completion, stop giving anesthetics and reverse any neuromuscular blockade (eg, neostigmine 2.5 to 5 mg IV with 1.2 mg atropine or 0.4 mg IV glycopyrrolate). Neostigmine is never given alone (or your patient will have severe bradycardia or cardiac arrest). Use a neuromuscular blockage monitor (neurostimulator) so that any muscle relaxations are well restored. Allow spontaneous ventilation to resume. Check the breathing pattern visually and with a capnograph. Wait for the return of consciousness.  28 Extubation. As soon as the patient wakes up and begins to obey the commands, remove the suction cup with a large nose from the oropharynx, remove the air from the endotracheal tube cuff with a syringe and pull out the endotracheal tube. Connect 100% oxygen through the mask after extubation. Support the jaw, apply exposure to the oral airway, nasal airway, or other airway as needed to maintain good spontaneous breathing. Closely monitor the patient's breathing and the pulse oximeter (hold over 95%).

28 Extubation. As soon as the patient wakes up and begins to obey the commands, remove the suction cup with a large nose from the oropharynx, remove the air from the endotracheal tube cuff with a syringe and pull out the endotracheal tube. Connect 100% oxygen through the mask after extubation. Support the jaw, apply exposure to the oral airway, nasal airway, or other airway as needed to maintain good spontaneous breathing. Closely monitor the patient's breathing and the pulse oximeter (hold over 95%).  29 Transfer to the post-anesthesia care unit (recovery room). When the case is over and the paperwork is completed, bring the stretcher to the operating room and lay the patient on it, without reaching for the line and without turning off the monitor. Don't forget the oxygen cylinder and oxygen mask. Observe the patient's breathing visually. Keep your finger on the pulse while moving the patient (where applicable), but use the transport monitor for sick patients or in large surgical cases (such as cardiac surgery). Report to the Certified Nurse in the Post Anesthesia Care Unit and to the Anesthesiologist who operates the Post Anesthesia Care Unit (in difficult cases).

29 Transfer to the post-anesthesia care unit (recovery room). When the case is over and the paperwork is completed, bring the stretcher to the operating room and lay the patient on it, without reaching for the line and without turning off the monitor. Don't forget the oxygen cylinder and oxygen mask. Observe the patient's breathing visually. Keep your finger on the pulse while moving the patient (where applicable), but use the transport monitor for sick patients or in large surgical cases (such as cardiac surgery). Report to the Certified Nurse in the Post Anesthesia Care Unit and to the Anesthesiologist who operates the Post Anesthesia Care Unit (in difficult cases).  30 Streamline post-operative care. Take care of any leftover paperwork before leaving. This includes pain relief orders (for example morphine 2-4 mg IV PRN), oxygen orders (for example, 4 L / min nasal cannulas or 35% oxygen face mask), antibiotics, food and drink orders, and postoperative tests such as electrolytes and hematocrit. Try to identify any special concerns for your patient. If necessary, discuss the current clinical situation with the patient's family

30 Streamline post-operative care. Take care of any leftover paperwork before leaving. This includes pain relief orders (for example morphine 2-4 mg IV PRN), oxygen orders (for example, 4 L / min nasal cannulas or 35% oxygen face mask), antibiotics, food and drink orders, and postoperative tests such as electrolytes and hematocrit. Try to identify any special concerns for your patient. If necessary, discuss the current clinical situation with the patient's family

Tips

- DRUG DOSAGE NOTE. Doses and volumes discussed here are for typical adult patients. Adjustments will be needed for pediatric patients, debilitated patients, and patients with impaired renal, hepatic, respiratory, or cardiac function. Drug interactions can also affect dosing.Remember, the clinical dosage of a drug (and time) is as much an art as it is a science.

Warnings

- This article is aimed at medical students. Only licensed physicians or board certified nurse anesthetists should administer anesthesia. Small mistakes can lead to the death of the patient.